We Owe the First Amendment to Iranians

I learned a new word recently: democide—the murder of people by a government that has power over them.

Since late December, hundreds of thousands of Iranians across dozens of cities have poured into the streets to protest the Islamic Republic’s failure to meet basic rights.

They faced a merciless massacre, chanting “Marg bar Dīktātor—Down to the Dictator” day and night, flying the ancient Lion and Sun flag, symbolizing strength, sovereignty, and divine glory.

This is not a protest against religion. It is a protest against fanaticism—an uprising rooted in Iran’s civilizational memory of freedom, secularism, and the Zoroastrian ethic of Good Thoughts, Good Words, Good Deeds. This moral framework upholds a righteous cosmic order amid the perpetual struggle between good and evil.

That struggle runs through Iran’s modern history against tyranny. It includes the Green Movement after the disputed 2009 election, the “Woman, Life, Freedom” uprising of 2022–23, and intermittent protests sparked by economic and environmental crises. Each time protesters revised strategies, the state refined brutality.

This uprising is not chaos, and while foreign military intervention may not be the answer, there is an opportunity to support—and meaningfully join—through moral and civic action.

What sets the current uprising apart—even from Bloody Aban—is its scale. In a matter of days in early January 2026, thousands were reportedly killed by gunfire and explosives, compounded by a relentless propaganda machine determined to erase the evidence.

Shoes that once belonged to protesters in the aftermath of the Islamic Republic government and IRGC’s reported attack in the city of Rasht, Iran. Witnesses say that regime officials set fire to a popular marketplace, trapping people inside and opening fire on those who tried to escape, Jan. 8, 2026. (@ninaansary)

Iranians are emerging from a 20-day, near-total internet shutdown imposed around January 8, with some accessing the outside world through VPNs or limited satellite connections such as Starlink. Authorities claim the blackout is being lifted, but connectivity remains heavily filtered and observable, and, in many areas, unstable or uneven. Independent civil-society organizations face severe restrictions inside Iran, so casualty figures largely come from groups and networks operating abroad. Estimates range from several thousand deaths based on verified counts to as many as 30,000, according to reports citing alleged internal communications from Iran’s Ministry of Health officials, with many more people reported injured or detained.

Executions have not stopped. Neither have the protests.

Bodies reportedly line the streets in bags. Mothers search for their children; families are charged for the bullets that killed them.

If they cannot pay, the bodies may be held in morgues or buried without consent, sometimes labeled Basij militia to manipulate statistics. If families do get the body, they may organize a funeral—or bury their beloved in their gardens. Even using state media’s lowest figures, the killings over those days qualify as democide: comparable to Tiananmen Square.

As a second-generation Persian on my mother’s side, what strikes me is not only the violence, but the propaganda some outsiders accept to preserve a simplistic worldview—excusing mass murder if the blood-moneyed Islamist government opposes the “right” enemies.

Beauty as the Target

I come from a Baháʼí family, a persecuted religious minority in Iran. I grew up knowing the cruelty of the Islamic Republic: the imprisonment and torture of women, artists, poets, dissidents, and religious minorities; the erasure of beauty. The names—the Monas, Alis, Sabas, Nasrins—are not abstractions.

Still, I never imagined that speaking about this would be met not just with apathy or prejudice, but suspicion. As if Iranian Americans who want freedom—or who would die for it, as Americans say they would—must somehow be spies.

Ironically, that is exactly what the mullahs say.

Right before they execute you.

Inspiration for Freedom of Speech

The Cyrus Cylinder, the human rights charter by Cyrus the Great of Persia. (Wikimedia Commons)

So what does this have to do with Americans?

After all, we have our own problems.

Pre-1979 Iran is often called “Western,” but historically, the truth runs the other way. Freedom is not foreign to Iran. Individual liberty comes from Persian culture; one could argue the West is, in part, Persian rather than Iran being Western.

The First Amendment did not emerge in a vacuum in 1787; long before that, around 539 BCE, Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon. He issued what is often described as the world’s first human rights charter, recorded in cuneiform on clay and now known as the Cyrus Cylinder, declaring essentially that “everyone is entitled to freedom of thought and choice and all individuals should pay respect to one another.”

Thomas Jefferson owned and studied Xenophon’s Cyropaedia, which portrayed Cyrus as an ideal ruler. While no direct evidence shows Jefferson studied the Cylinder itself, the Persian conception of religious freedom represents the same river of Enlightenment that shaped the United States founding principles.

If Cyrus had not acted decisively, Babylon might not have fallen, and the United States might not have its First Amendment.

At minimum, each of us—regardless of our views on intervention—can speak. We can use the freedoms we have inherited to lift the voices of the Lions, Lionesses, and their cubs calling out in remembrance of liberty.

As Marjane Satrapi said:

“You are American, I am Iranian… The difference between you and your government is much bigger than the difference between you and me. And the difference between me and my government is much bigger than the difference between me and you. And our governments are very much the same.”

For better or for worse.

Iran and America’s Textured Century

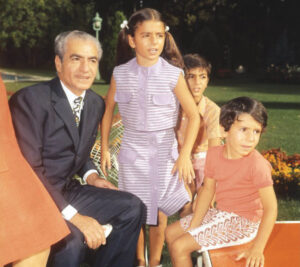

Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and his children, Farahnaz, Reza and Alireza at Niavaran Palace, 1971. (Wikimedia Commons)

While some may imagine a U.S. military solution, history and the complexity of Iran’s society caution against it.

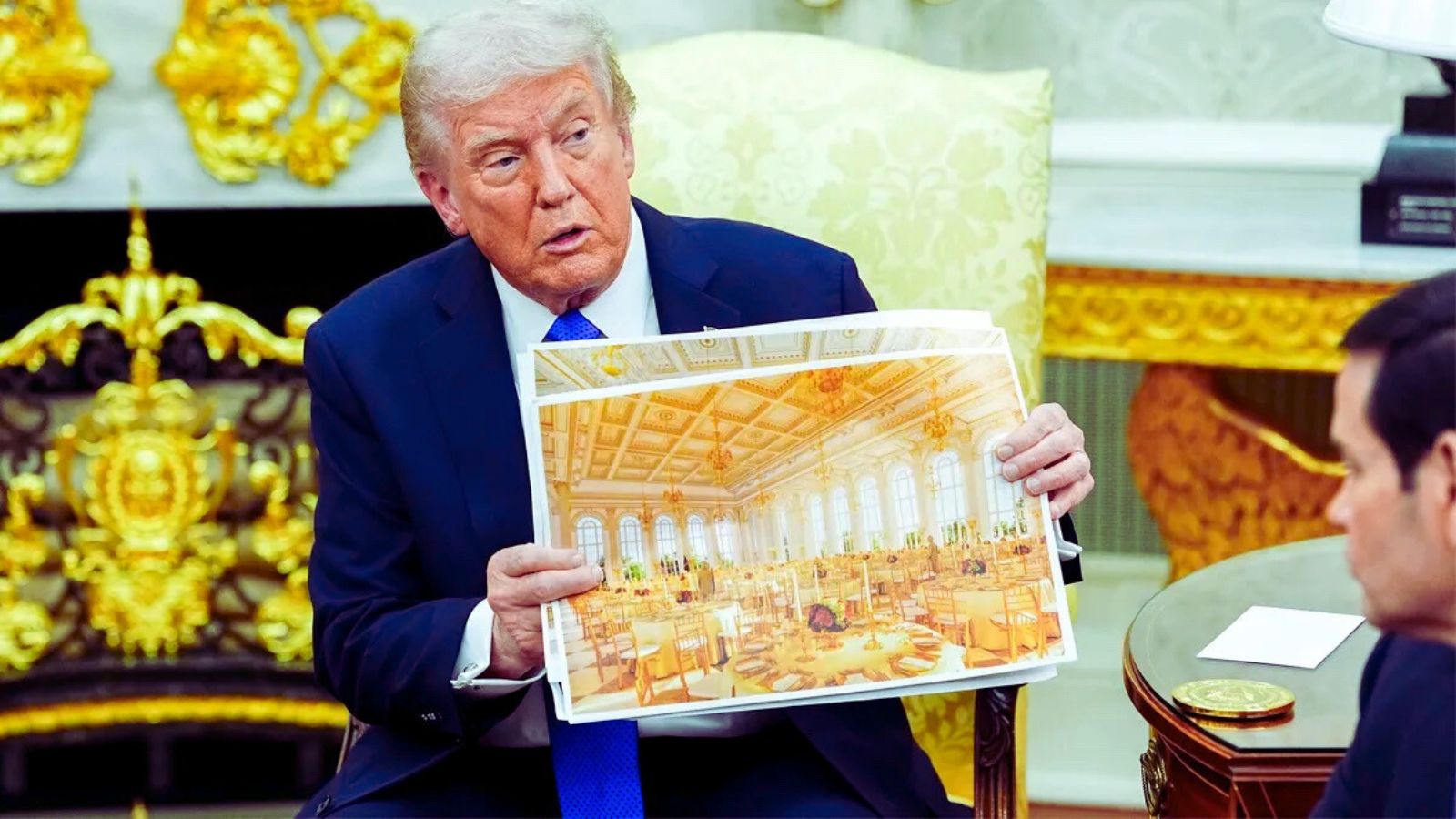

Reza Pahlavi, the exiled son of the last Shah, reemerged as a central, controversial figure in the current uprising. Exiled in 1979, he is supported by parts of the diaspora and many inside Iran calling for a transition to democracy. He has said he does not seek the throne, only free elections. Blending nostalgia with forward movement, he greets his supporters as “My Compatriots.”

On January 18, 2026, Iranian state broadcasts were briefly hacked to air his message, urging Iranians and security forces to rise as patriots, not enemies. He said, “Don’t point your weapons at the people. Join the nation for the freedom of Iran.” Wherever one stands on his politics, it was a brave, bold, big-hearted move. And it worked. Several regime members publicly defected.

While today the majority are for the transition to democracy, Iran has long been caught between secular governance and religious authoritarianism.

The Pahlavi dynasty began in 1925, when Reza Shah rose to power idolizing the West. His decree banning the veil was enforced coercively, including police forcibly removing it from women in public. For some, it was liberation; for others, terror. Freedom for some, oppression for others—both forced.

As Margaret Atwood wrote in The Handmaid’s Tale, partly influenced by the Islamic Republic’s early occupation of Iran:

“There is more than one kind of freedom… Freedom to and freedom from.”

His son, Mohammad Reza Shah—the last king of Iran—wrapped his rule in ancient Persian traditions. The royal family, he, Queen Farah, and the children (including young Reza), dripped with jewels and joy, celebrating Zoroastrian fire and the renewal of spring. The Shah promoted religious tolerance relative to what followed. Freedom at last, or so it seemed.

Then came Mohammad Mosaddegh. He nationalized the British-owned oil industry; the U.S. and the U.K. intervened. Fear of communism dictated control. From there, the story hardened.

The Shah returned with reforms: land redistribution, free school nourishment, women’s suffrage, protection for religious minorities.

Iran had oil wealth, but the people rarely saw it. Many loved him; many despised him—not for reform, but for a system that modernized life while denying political and social voices.

The Shah gave his people nearly everything except freedom of speech. His secret police disappeared critics. The silence grew heavy.

When the Islamic regime was starting to seize power, the Shah’s minister of information, Daryoush Homayoun, warned:

“If the leftists or Islamists take over, you won’t be as free as you are now; they are totalitarians and we are not. Now is the time to choose.”

The warning was ignored. The leftists were treated as useful tools—among the first to be persecuted.

However, for the Shah, oil was not the most precious resource, but rather the land itself. Grasping a handful of soil, he left the country on January 16, 1979. One elder in my family said, “If you had a father that did good but was not perfect, he was still a father.”

He found fleeting refuge in the Bahamas, then sought treatment in Mexico for leukemia. Many urged him to go to the United States. He replied, “How could I go to a place that had undone me?”

He eventually relented. In Panama, one of Ayatollah Khomeini’s advisers demanded the CIA kill him. Frightened, he fled to Egypt. Beneath his hospital bed, according to family accounts, he kept a bag of that Iranian soil. He died on July 27, 1980, buried with the earth of his homeland.

A Baháʼí Family History

As upheaval grew, my grandmother urged my mother to leave Iran. It did not quite feel like fleeing, nor permanent. Yet on the day of my mom’s flight, a solemn vibration rumbled on that front step. A mother hugged her daughter for the last time.

When the Islamic Republic was installed, religious minorities such as Bahá’ís were persecuted as well. An elder in my family nobly penned dignified appeals to authorities. From prison, he wrote to his daughter—opening with prayer, then eventually surrendering his fate to God.

And humbly, with an almost otherworldly grace, when appealing to the government, wrote, “I apologize for the length of this letter.”

In 1991, the regime formalized persecution in the memo “The Baháʼí Question,” designed to block Baháʼís from education, employment, and livelihoods. It remains in effect.

Barred from universities, Baháʼís created a network of educators online—Education Is Not a Crime. Iranian society remains educated and religiously diverse.

Human Rights Are Not a Crime

Demonstrator during the 2025–2026 Iranian protests silhouetted against a street fire, waving the Lion and Sun flag. (@gghamari)

But the populace is not the government. Executions, hangings from cranes, invasions of innocents’ homes, theft of property, and snipers aiming for eyes—none of this is new.

That is why the regime must fall.

Regime change does not require U.S. military intervention. People have toppled governments before with little foreign involvement—Romania in 1989, East Germany with the Fall of the Berlin Wall that same year, among them.

Still, the international community has commitments. The U.N.’s Responsibility to Protect (R2P), which evolved from failures to act in Rwanda and the Balkans, affirms that sovereignty does not excuse mass atrocity: “If a state fails, the international community must act—peacefully, or coercively—to protect vulnerable people.”

Faith, Truth, and Our Common Humanity

Photo by Daria Sukhorukova. (Wikimedia Commons)

When pointing to the Islamic Republic, it is essential to differentiate between peaceful, beautifully practicing Muslims and Islamism, an ideology that wields religion as power. The sword given to the Lion originally signaled military force, and what is often interpreted as a tulip-like calligraphic rendering of ‘Allah’ on the current Shi’a Islamist flag, drawing on a Persian floral symbol of lost children, resonates somberly after the 2026 Iran Massacre.

Persian culture is comfortable with complexity but also has a moral backbone.

As Saadi, who was a Sunni Muslim, wrote:

Human beings are parts of one body,

In creation they are indeed of one nature.

If a body part is afflicted with pain,

Other body parts uneasy will remain.

If you have no sympathy for human pain,

The name of human you shall not retain.

Some of the most sympathetic individuals are the poets, nomads, and martyrs of principle rather than politics.

Around the world, people are fed up, echoing Free the People’s motto: “Don’t hurt us. And don’t take our stuff.” But the Iranian people do more than fight with fist and fire. They sing. They dance. They live.

During the Qajar and Pahlavi periods, the sun with the lion bore the feminine features of Anahita—a Khorshid Khanum. Equality was not foreign to this land.

The revival of Persia—the birthplace of human rights, a wellspring of Enlightenment ideals, and a millennia-long struggle to discern good from evil—may yet be a key to unlock a deeper peace, both abroad and at home.

Many Americans are cautious about intervention, rightly concerned about the consequences of foreign military action. Yet even from restraint, there are ways to join Iranians’ uprising for liberty: support uncensored internet access, amplify independent reporting, speak thoughtfully about fanaticism, and pursue strategies to counter any authoritarian influence—even these acts of care matter.

“Whether peace is to be reached only after unimaginable horrors… clinging to old patterns of behaviour, or is to be embraced now by an act of consultative will, is the choice before all who inhabit the earth.” —Baháʼí Writings

And in the words of my ancestor, with equal urgency and humility:

Please forgive me for the length of this letter.

Free the People publishes opinion-based articles from contributing writers. The opinions and ideas expressed do not always reflect the opinions and ideas that Free the People endorses. We believe in free speech, and in providing a platform for open dialogue. Feel free to leave a comment.