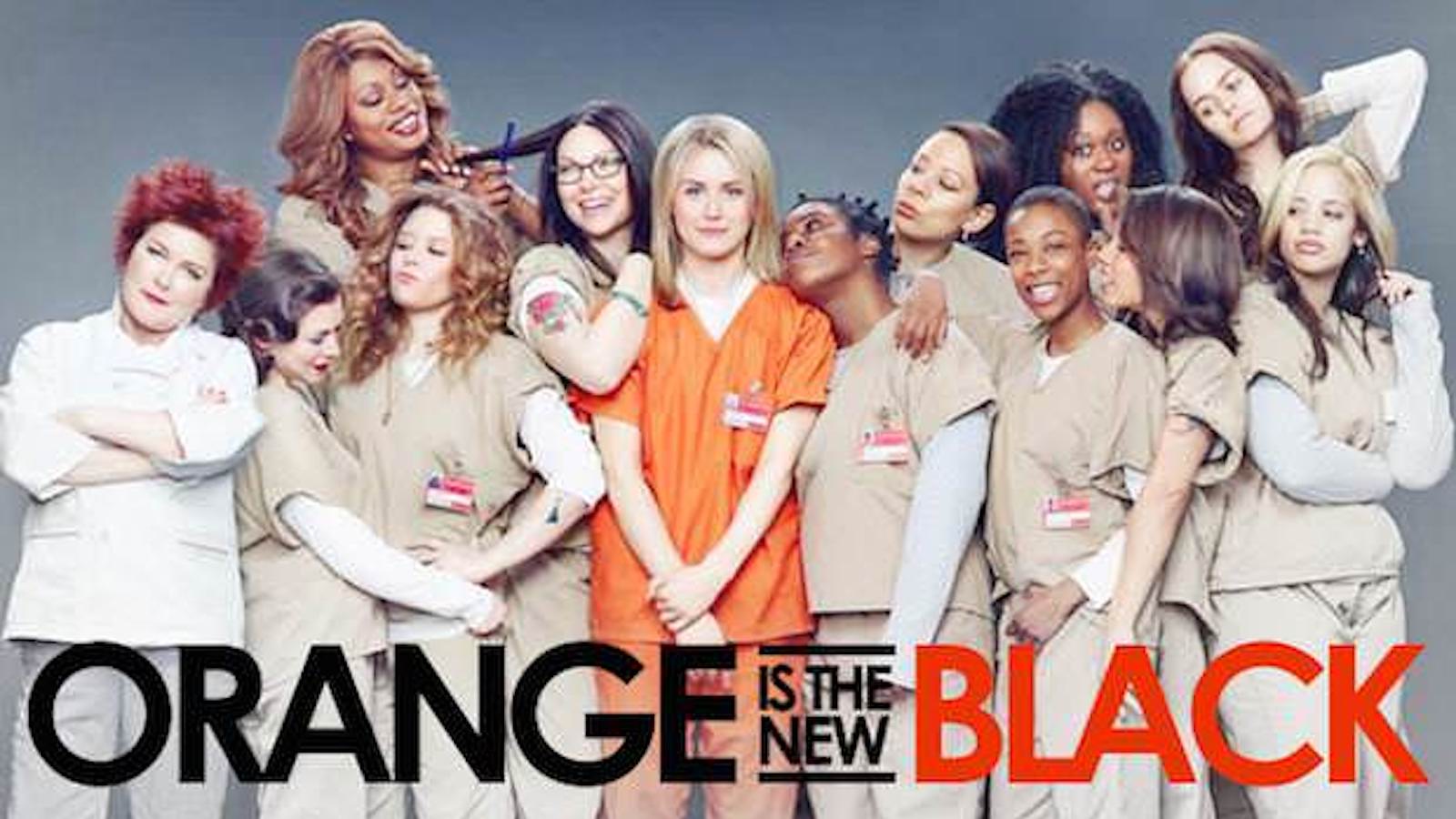

Orange Might Be Your New Black

The new season of “Orange Is the New Black” soon comes out on Netflix, and I’m excited. The last season was tremendously revealing. It showed us a side of life that we don’t usually get to see, the life of prisoners, in this case, all women.

We don’t really want to see it. When people go to jail, they disappear from society, as if dead. It pains us to think about them, so we do not. We block them from our minds. If we do think about them, we are tempted to be glad it’s them and not us. Surely they made some terrible mistake that we won’t make.

Meanwhile, the prisoners can’t be snapchatted or tweeted. We can’t see their status updates because they have no social media. The only way to contact them is to write letters that are read by others. We can’t even visit most of them, and, when we do, our conversations are restricted and monitored. It is somehow easier for us to forget about them.

But this is cruel and inhumane.

There are no greater victims of state despotism and public-policy injustice than those who are members of the prison population. Yet they figure into no political campaigns except for the periodic boorish and blustering speech by a demagogue who calls for ever more people to be put in the slammer, as if justice can ever be achieved this way.

No matter how much we don’t like to look or think about this topic, we should because the United States is the home to the largest per capita prison population in the world. You might know someone who is there right now, or, at least, knows someone who knows someone who is there.

How close is the jailer to our own door? Very close indeed. No one is safe in a society ruled by the prison state.

You know what you quickly find when you go to jail? You find that people do not lose their humanity when they go to prison, and this show reveals this so beautifully. Prisoners still have aspirations, feelings, emotional needs, particular tastes, brains, and souls. What this means, in the end, is that they cannot finally be controlled.

There are constraints, enforced by coercion, as with any aspect of life. People both in and out of prison face that. And what do people do? They form a society. They figure out ways to trade. They assemble based on human volition, tribe, interest. They work the system. They make the system work for them. The results are gravely distorted and strange but they are better than if free will did not exist and everyone just walked around like zombies.

All of this is on display in the show. The social networks are complex and ever-changing. The race relationships are fascinating.There are deep friendships and intense hatreds. There is trade and entrepreneurship. Every vice and virtue is on display in infinitely changing combinations. Yes, it is jail but only in a physical sense. Otherwise they are free to think and dream and make lives for themselves as best they can. And they do exactly this.

This is why the show inspires me. It demonstrates that no one is a robot. They might pretend to comply. But they don’t really comply. Every single woman in this prison figures out very quickly that compliance could mean disaster. So even under these extreme conditions, they work out a system around the system. They find the flaw and exploit it.

Why are the women in prison? We are being given the back story on each person as the series progresses. Sometimes it is about some terrible crime like murder — and yet, the more you look at the circumstances, you kind of get why it happened (vengeance for another injustice does complicate matters). There are other real acts of violence and theft, though one wonders what precisely is being accomplished by locking these people up, since they are paying no one back and living out no realization of justice.

There is the matter of drugs. More than half of U.S. prisoners are in there for this reason or some other nonviolent crime (such as not paying child support or taxes). Also, and ironically, drugs are a huge deal in prison. Yes, narcotics get in, despite the drug war, despite prison, despite high security. Why are these women in jail for drugs when their jailers themselves are accomplices to the furtherance of the drug trade in prison?

It’s because the whole system is a lie from top to bottom. Prison is a particular kind of hell because of the intensity of the demands for compliance with arbitrary rules. But in the end, there really is no such thing as prison as exists in legend and lore. There are only various degrees of coercive constraint, none of them finally capable of creating order. If order exists, it is because we create it ourselves. That’s the message of this series.

What’s especially interesting is the prisoners’ relationships with their jailers. The guards don’t really believe in the system either. They are all “corrupt,” which is to say they too are human. Why do they do what they do? Because it’s their job, and they signed up to do it.

The guards pretend to guard and the prisoners pretend to comply. And they bide their time until a better opportunity comes along. In this sense, the distinction between being inside prison and outside prison begins to blur. It’s this way with most functionaries of the nation-state. It’s just something they do, something they endure until another better thing comes along.

Maybe they are in there for deterrence for others? But they are not deterring anyone while in prison. Clarence Darrow, writing in 1902, observed that if we really want a system to deter people, we would drag a huge iron pot of boiling oil in front of the courthouse and lower all these people into it, lift them out, and show their fried corpses to the assembled masses.

But the state doesn’t do that. It keeps them out of sight and hides their sufferings from our eyes as much as possible. This is especially true when the state kills people. It brings in doctors in lab coats, lawyers with binders, and priests with stoles. The deed is done in a sanitary basement where no one else can see.

Why? Darrow observes that when people can really see what the state is doing to people, they don’t cheer; they are disgusted and turn on their leaders for their cruelty. They overthrow regimes. That’s why the sufferings of prisoners are hidden from us. It is a method protecting the state from public anger that inevitably results when average people become conscious of the reality of prison.

What sustains such a wicked system? The law, most of it enforced by bureaucrats that don’t believe the lie that anything good is being accomplished; the law, most of it passed by legislators who long ago left office; the law, approved and sustained by jurists who believe it is someone else’s job to ask fundamental questions of right and wrong; the law, believed by average people to have something to do with justice only because they do not know and do not want to look at the ghastly reality that there is no justice.

The prison is a relic of the cruelness of an age that is passing, and it will surely be one of the last surviving elements. This will remain true so long as we as a people maintain a studied and deliberate ignorance of the egregiousness of this sector of life. We are comfortable doing that — until that fateful day when we find ourselves on the other side of the wall and are left only to hope and pray that someone on the outside cares enough to make a change.

I once knew a man who said that he conducted a choir. I asked where his choir is. He said it is made up of death-row inmates. He goes weekly to train and direct them, and they sing just for themselves. Every few months, he loses a member and a voice goes silent. This is a great man. Let us not only weep for those silent voices. Let us work to dismantle the system that is silencing them.

Free the People publishes opinion-based articles from contributing writers. The opinions and ideas expressed do not always reflect the opinions and ideas that Free the People endorses. We believe in free speech, and in providing a platform for open dialogue. Feel free to leave a comment.

John Jones

Well done Jeffrey.

I guess I now have another series I have to catch up on after I get through The Wire.

Audra Flammang

I resisted this show for so long, precisely because it was a show about prison. I finally gave it a chance and then binge the rest of the season. About halfway through the season I got to where I would tear up at the Regina Spektor song in the opening credits 🙂 I love the back stories for each character. Thank you for articulating what makes this series so wonderful.

By the way, when I was discussing this show with a friend, she recommended this book to me. Haven’t read it, so I can’t truly recommend, but she said it was Wally Lamb’s attempt to give women in the prison population a voice.

Adam Hoisington

This is great, Jeff. You’re so right about forgetting about prisoners and the whole morally bankrupt system.

My only regret about TV shows these days is that there are too many great ones to keep up with them all. This is one I have not watched yet. I’ll make a point of it, though.

Adam Hoisington

This is great, Jeff. You’re so right about forgetting about prisoners and the whole morally bankrupt system.

My only regret about TV shows these days is that there are too many great ones to keep up with them all. This is one I have not watched yet. I’ll make a point of it, though.

Jack Feka

I quite enjoyed this series when I watched it but I never thought about it in depth the way you have in this article, although I’m sure most of the enjoyment which I felt was due to the undercurrent of the kind of things you’ve elucidated.

It’s a pity that more people don’t analyze the reasons why they like or dislike something even to a much more superficial level than you have (and I include myself in that). In my case, at least, I think it may be because I haven’t had a lot of contact with people who are willing to discuss experiences on this level. I don’t mention that as an excuse, but simply to observe that if we don’t have an opportunity to exercise an ability, we’re not likely to become very adept at it.

This, perhaps, may be one of the greatest benefits which Liberty.me might offer individuals like myself.

Daniel Davis

I love this show. It’s hard to see Dagny Taggart in prison though.

Antoinette Sopocko

Beautiful. Never seen the show (no Netflix subscription) but you’ve given us food for thought.

Antoinette Sopocko

Beautiful. Never seen the show (no Netflix subscription) but you’ve given us food for thought.

Jack Feka

I re-watched the entire series in preparation for season 2 and wonder if the conditions in prisons are as dramatic and intense as they are presented in this and other movies and programs.

Since I’ve not had any personal experience in a prison, nor do I have any close friends or family watching this again made me aware that virtually all of my perception of what life is like in a prison has come from movies and TV shows.

Can anyone enlighten me?