Principles of Human Action

February 26th, 1995

Lecture Number Two

As we begin lecture two you should keep this in mind about the ideological immune system. Again, and I can’t overstress this, everyone has one. Let’s look again at how it operates. Your ideological immune system rejects your acceptance of any new basic ideas that would overturn any of your old basic ideas.

You will find that most adults never suppress or hold back their ideological immune system. The result is they are fully protected 24 hours a day from new ideas, and especially they are protected from new major ideas and revolutionary ideas.

Here is one result of their protection: the Locke, Planck, Mises Problem. Educated, intelligent, successful adults rarely change their most fundamental premises. Now, if you happen to live in a static society where little or nothing changes from one decade to the next, or from one century to the next, then it doesn’t matter because there are no new ideas being generated to be rejected in the first place. The medieval or feudal society was such a static society. But the more advanced the society, the more rapid the social changes and those who do not embrace new ideas will get left behind.

Here is a question for us to consider: when should you suppress your ideological immune system and embrace a new idea? As you likely discovered long ago, a new idea does not necessarily mean a better idea. New is not equal to better. If we embrace every new idea that comes along, what does that mean? We will be embracing a lot of bad new ideas, won’t we? A new bad idea is not likely any better than an old bad idea.

The problem then becomes how can we distinguish or differentiate between a good idea and a bad idea? You will see that you can approach the problem in really only two ways. One, you can make this determination scientifically or, two, you can make the determination unscientifically. That covers all possibilities.

From what has already been said it should come as no surprise that our approach will be what? Scientific. And what is it that scientific methods can do that unscientific methods cannot do? What do you think has brought about all of the amazing scientific progress of the past 300 years? The methods of science have given us better and better explanations of the causes of things, the causes of effects.

Sometimes science replaces a false explanation of causality with a true explanation. Sometimes science replaces a complex explanation of causality with a simpler or more elegant explanation. Sometimes science replaces a tentative or uncertain explanation of causality with a definite or more certain explanation. When these advances in our understanding of causality are achieved, it’s really not a time to mourn, it’s rather a time, at least for me, to rejoice.

Two thousand years ago, the great Roman poet Virgil gave us a model we can use for the entire seminar. His idea on cause, the cause of happiness, still rings true today. He said, happy is he who has succeeded in learning the causes of things. For three centuries science has advanced our understanding of causality. There is no reason to believe this trend will ever end.

But this raises another question: If science is the greatest problem-solver and solution-builder there is, then why do the problems of society appear to be growing larger rather than smaller? Have you ever thought about that? To answer this question, I will give you another question. It is one of the more important, and I think embarrassing, questions of this century. If we fail to find a scientific answer to this question, I’m afraid civilization will perish.

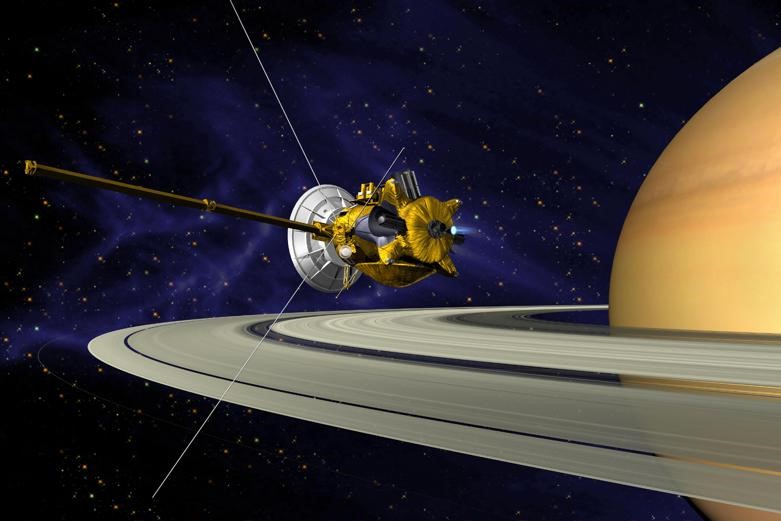

The question is this: if we were smart enough to send a vehicle on a 750-million-mile journey to Saturn; if we are inventive enough to command the cameras on board to send back spectacular photographs like this…

…if we are intelligent enough to not only land a man safely on the surface of the moon, but to bring him back alive, which is even more remarkable; then why, dear friends, aren’t we smart enough, inventive enough, intelligent enough, to bring to an end all of these seven crisis problems?

For example, let’s look again.

Crisis one: International war. For decades we’ve been averaging something like 30 or 40 wars going on at any one time in various parts of the world. But because the battles usually are not fought in, let’s say, places like California or Kansas, most Americans at least are not too concerned about them.

These wars are called conventional wars fought with so-called conventional weapons. However, in time there is nothing to prevent conventional wars from turning into unconventional wars, where they drop convention and start throwing around nuclear, chemical, or bacteriological weapons. The risk of this happening continues, of course, to increase.

Crisis two: World starvation. Most people who gather statistics on world hunger tell us that more than a third of the world population, a third of the men, women, and children on the planet, suffer varying degrees of hunger and starvation.

Crisis three: Widespread poverty. Where there is hunger you can be certain there is a lot of poverty, which means there is a general scarcity of the necessities of survival including food, clothing, and shelter.

Crisis four: Economic depression. Widespread business failure and stagnation continues throughout much of the world.

Crisis five: Currency inflation continues to erode the standard of living of the people in many nations throughout the world.

Crisis six: Epidemic crime. Crimes of robbery, burglary, assault, continue to escalate in our cities, suburbs, and they’ve now intruded into the once-secure countryside.

Crisis seven: Failing education, where it is commonly publicized that a half to a third of the high school graduates are illiterate and more than 40 million American adults cannot read. Many, perhaps some of you, attribute this to the failure of the educational system to educate.

These seven crisis problems affect us directly and indirectly. Together they present this compelling question: if humans are smart enough to go to the moon, then why aren’t we smart enough to resolve these seven crisis problems? How would you answer what we might call the most embarrassing question of this century?

Most people, if you press them, will offer some kind of an opinion. But can we do better than mere opinion because who is to say that one opinion is better than another? Opinions usually involve beliefs that cannot be supported with scientific observation or confirmation.

In this seminar we’re going to focus on finding scientific answers to these questions. If it is a scientific answer, then you can use the same scientific method I used to come up with the same answer. Therein lies the power of science. The scientist says, here are my data, here is how I conducted my experiment, here are my results and conclusions. Then he says, now you try it, independently of me. Do everything I did, and then you see if you can come up with the same results.

That’s how science works. When other independent experimenters come up with the same results, that’s scientific confirmation and the confirmation makes it more than mere opinion. Just as an aside, almost all opinions all the time are worthless. There’s hardly an exception. Opinions never solve any problems anywhere. They usually prevent problems from being solved. What is the quality of your opinion? These are questions we’ll answer in this seminar.

Here is one reason we failed to end these crisis problems: there has been a general failure to apply the methods of science to correctly identify and understand the causes of these seven crisis problems. How can we succeed then in learning the causes of things, especially the causes of the effects that you like and you dislike? Those are the ones you most want to know about, right? What causes the things you most like and what causes the things you most dislike? The others are less important, aren’t they?

Since the dawn of human existence, there have always been a few people more curious than others, eager to understand the causes of things. We do not fully understand why some people have an extraordinary desire to understand causality but we can presume that some combination of genetic and environmental inputs makes it so. I don’t know why it is.

Because we are surrounded by nature, a few of our more curious ancestors were eager to understand the causes of things in nature, the causes of natural phenomena. For example, whenever and wherever you live, the phenomena we call weather is hard to ignore, especially when it comes in the form of lightning and thunder. Man has observed and felt the effects of the weather from his earliest beginnings, but only in the last three centuries have we gained a correct understanding of the causes of weather phenomena.

When we study natural phenomena we are looking for the causes of physical things. This bolt of lightning I photographed on my front porch probably over 30, 35 years ago, is a physical thing. The physical sciences then involve the study of the nature and causes of physical actions.

Three hundred years ago the founders of modern science developed a method to study what’s going on in the world and it’s called the scientific method. Since then it has proven to be the method of methods for understanding causality. And so, we use this scientific method to investigate the causes of very small physical things such as these atoms and electrodes.

On the screen is a photographic plate that was exposed in a physics lab using what’s called bubble chamber technology. These tight spirals are the tracks made by electrons.

At the other extreme, when we turn to the study of very large physical things, the same scientific method is used to investigate the causes of galaxies composed of hundreds of billions of stars.

This is a photographic plate of a galaxy, exposed in an astronomical observatory.

The scientific method explains the causes of physical things so well, we have successfully applied the method to build these giant skyscrapers.

We’ve used the same method to build these commercial airliners.

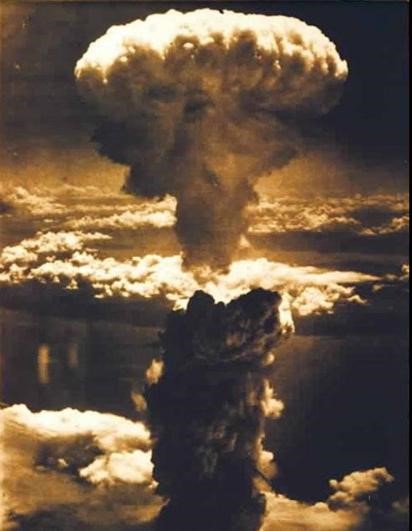

But unfortunately the same method of understanding the causes of physical things, has also been used to build, as you know, nuclear bombs. Well we cannot create these bombs without creating a crisis at the same time. It’s well-known that the detonation of just a few of these bombs will generate the destructive force equivalent to all of the TNT bombs unleashed upon soldiers and civilians in World War II.

Virtually everyone would like to avoid the repetition of a scene such as this one where one relatively low-powered, tiny, atomic bomb obliterated what was once a Japanese city.

By now of course we’ve seen these pictures. You’ve all seen this picture many times. You’ve seen this so many times it becomes what might be called a photographic cliché and it pretty much loses its impact.

Nevertheless, for decades, many members of the scientific community have been voicing their concern that the very existence of these bombs endangers the very existence of our human race. The Cold War may be over, but this does not lessen the threat of the probability of nuclear war. It is still unclear where the Soviet’s vast nuclear arsenal will be deposited. Weapons may eventually wind up in more political hands rather than fewer political hands, which means what? More risk or less risk? More risk.

The question for us to examine is: how did we get ourselves into this crisis, wherein we face the potential destruction of civilization? The question is crucial. Why is it crucial? Because, friends, if we can understand how we got ourselves into the crisis in the first place, guess what? That will give us a clue on how to get out of the crisis.

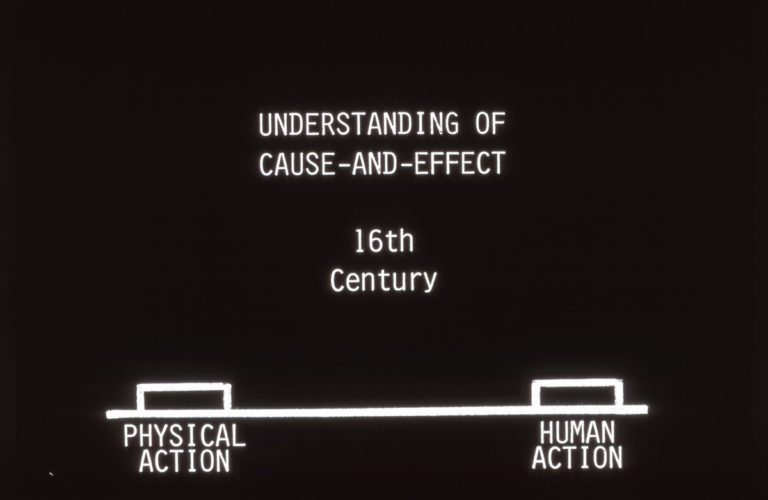

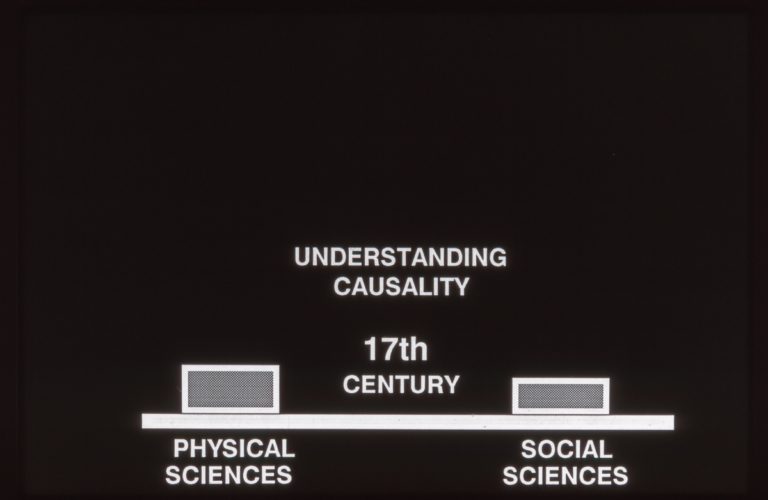

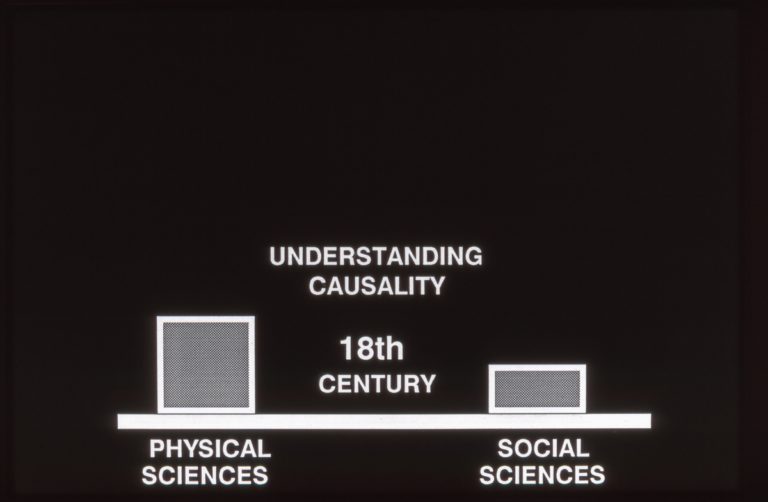

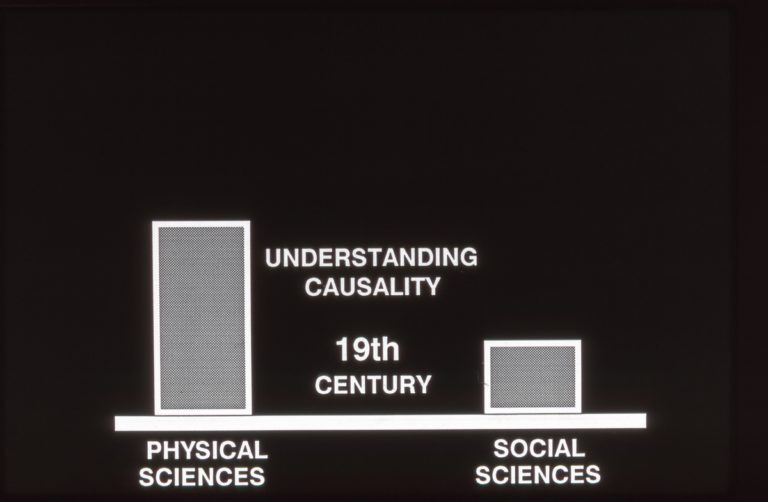

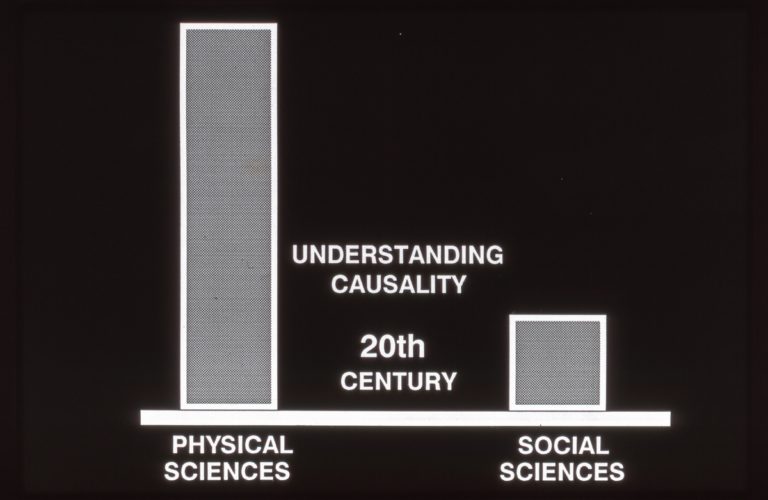

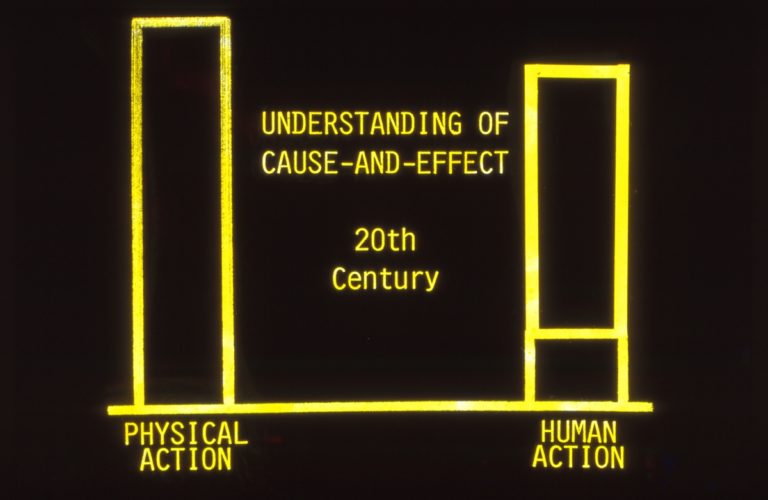

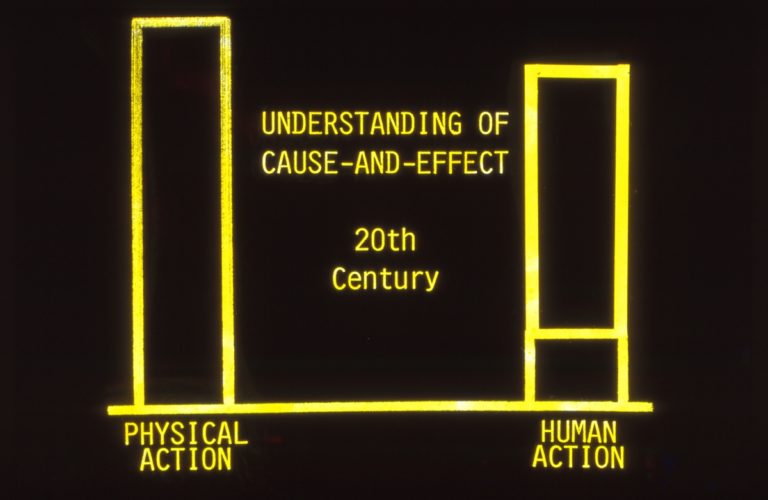

Here’s what’s happened: there’s been a disparity between the progress that’s been made in the physical sciences, and that which has been made in the social sciences. This bar graph illustrates the contrast between the growth of our understanding of causality in the physical sciences versus the growth of our understanding of causality in the social sciences.

In the 16th century the level of our correct understanding of causality in the physical sciences was roughly comparable to what it was in the social sciences.

Now, going on to the 17th century, our understanding of causality in the field of the physical sciences moves a little bit ahead of our understanding of causality in the social sciences.

Then as we go on to the 18th century, our correct understanding of causality in the physical sciences has now moved sharply ahead of our understanding of causality in the social sciences.

As we look at the 19th century, the trend becomes more noticeable. The rate of growth of our correct understanding of cause and effect in the physical sciences is moving much more rapidly than the rate of growth of our understanding of causality in the social sciences.

Finally, we look at the 20th century, and we have a graphic illustration of the cause of our own century’s unparalleled social crisis. I call this the geometric-arithmetic social crisis. The imbalance between the growth of progress in the physical sciences with those of the social sciences has reached a critical point.

For the past 500 years, the growth rate of our correct understanding of causality, the growth of progress in the social sciences, has approximated what is called an arithmetic progression. You are familiar with these terms if you have a background in mathematics or science. We’re now going to go through the five graphs just a little more rapidly and you can see essentially what has been happening here – 17th century, 18th century, 19th century, 20th century.

The mathematical nomenclature that describes the difference in these growth rates, many of you already know. For the past 500 years, the growth rate of our correct understanding of cause and effect in the human action sciences, or social sciences, has been an arithmetic progression. In rather sharp contrast, the rate of growth of our correct understanding of cause and effect in the physical sciences or physical action sciences, has been a geometric progression.

However, it is not necessary to understand the mathematical distinction between these two progressions in order to recognize, I hope at least, that the difference between the growth rates is rather dramatic. The potential difference makes waves, waves that have the potential to drown all of civilization.

Where do we go from here? Let’s follow some advice from one of the smartest men of the 20th century.

Since 1905 this man’s reputation has continued to rise as we find more and more scientific evidence to support his scientific views. All of you recognize who this is. Usually we see his picture as an old man with gray hair riding a bicycle or something. Albert Einstein tells us that the formulation of a problem is often more essential than its solution, which may be merely a matter of mathematical or experimental skill.

The problem we have to solve is how can we go from this situation to this? How can we do this?

That’s graphically what the entire solution looks like. If that is a solution, how can we do this? Where do we start?

I’ve labeled the problem, the geometric-arithmetic crisis. The fact that you can have such a crisis in the first place was recognized 200 years ago by an English clergyman, and one of the founders of the science of economics. Many of you have heard of him, Thomas Robert Malthus. Malthus was one of the first to attempt to apply mathematical concepts to the study of human action.

In 1798 he published his famous essay, An Essay On The Principle of Population. Malthus shocked the intellectual world of his time with this disturbing sentence. He said, “population, when unchecked, increases in a geometrical ratio. Subsistence only increases in an arithmetic ratio.” Malthus was saying that if we don’t do something to check the population growth, a catastrophe is inevitable.

And so we have the difference between these two progressions, an arithmetical progression as moving for example 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 versus a geometrical progression, which is 1,2,4,8,16,32,64,128. So he is saying essentially that units of people will increase at a geometric rate, while units of subsistence to sustain these people will only increase at an arithmetic rate.

In the second edition of Essay on Population, he pointed out that these mathematical ratios cannot be carried out indefinitely. But he made his point and he’s still making his point. Today we can witness the operation of the Malthusian geometric-arithmetic crisis in the impoverished nations. The people are producing units of subsistence at an arithmetic rate, while they’re producing units of babies at a geometric rate.

You can drop the mathematical language and use plain old street language. These people are producing babies a hell of a lot faster than they’re producing food. The result is dramatic! It is called starvation and famine.

Now with regard to the mathematical ratios that compare the progress of the physical sciences with the progress of the social sciences, like Malthus, I’m not claiming these ratios can be precisely measured or quantified. The concept of the geometric-arithmetic crisis is a mathematical metaphor.

As you know, a metaphor is a figure of speech that’s not intended to be completely literal. Nevertheless, the metaphor accurately describes a real crisis, because where babies are produced at a geometric rate and food is produced at an arithmetic rate, that is a real crisis. And where the physical sciences are progressing at a geometric rate and the social sciences are progressing at an arithmetic rate, there is an ever greater crisis.

A critical question follows: how can the social sciences catch up with the physical sciences to prevent an ultimate catastrophe?

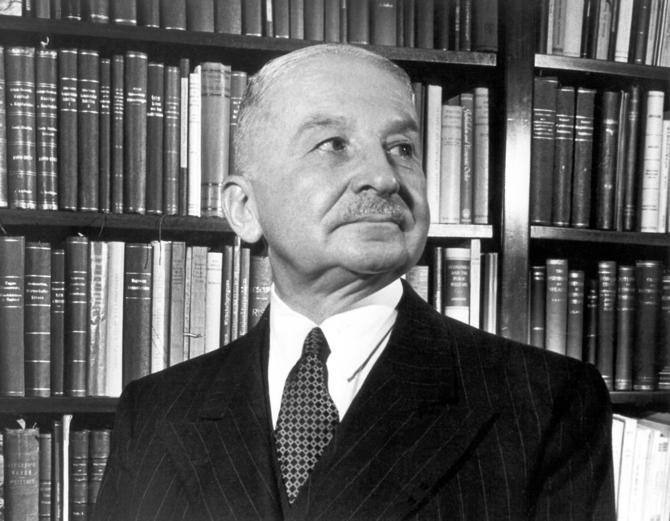

A contemporary of Einstein’s, the man shown on the screen, has given us an important clue on how to do this. He’s the late Dr. Ludwig Von Mises, Professor of Economics and Law. What I call optimization theory is a major extension of the science of human action, introduced by Professor von Mises in his major publication, Human Action.

On page two of Human Action, Von Mises shows us the path we can follow to achieve a rapid acceleration of our understanding of the causes of human action effects. He says, in one sentence, “one must study the laws of human action and social cooperation as the physicist studies the laws of nature.” The key to understanding physics and physical action is to focus on understanding the physical laws of nature.

To illustrate, let’s assume it’s the middle of the 1930s. We’re going to have a physical action problem to solve and that is how to build a suspension bridge with a 4,200 feet span over the entrance to San Francisco Bay. How can we do this before the bridge is built? It will have to look something like this.

The center span will have to be 700 feet longer than the longest span ever built, which was its predecessor The George Washington Bridge in Manhattan, which was 3,500 feet. That was over the Hudson River in 1931.

The towers at each end of this span will rise to a record – this is before it was built – of 265 feet, and the foundation of the south tower, which is closest to you, will have to be built under 85 feet of water. They’ve got to build a tower under 85 feet of water and not just still water but with rapidly moving currents.

How can such a bridge be built, especially when most of the bridge experts building bridges in the 1930’s are saying what? It can’t be built. Exactly! You got it. It cannot be built. Design engineer Glen Woodruff and chief engineer Joseph Strauss certainly must have had a thorough understanding of the physical action laws that apply to the technology of bridge building. What do you think? They must understand the physical laws of nature that, when correctly applied, will cause the bridge to what? To be stable to support loads of vehicles and to be durable. Principles of physics will cause it to do all of these things.

What principles are they? Let’s find out, they say. Without a thorough understanding of these laws and how to apply them successfully, the bridge would be unbuildable. It could not be built in a hundred years or a hundred hundred years. But now let’s change the problem from a physical action problem to a human action problem.

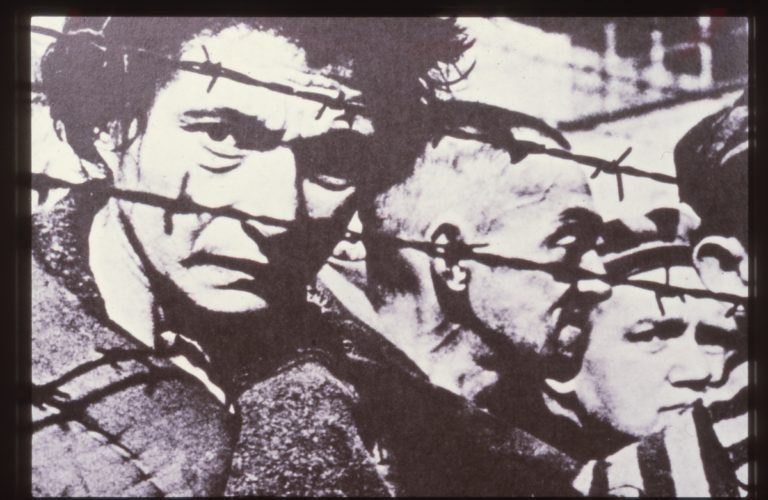

On the screen is a human action problem. You immediately recognize this as some kind of a war scene. Is that pretty clear? Some kind of a war scene. Wars always cause deaths and injuries to vast numbers of people. They cause destruction to vast amounts of property. This is known to everyone. Even children know this. And so we have a human-caused problem that will require human action to solve.

Instead of building a bridge, which is a physical action problem, we want to build peace, for example, which is a human action problem. Well one of the first difficulties to overcome is this: most of the educated, intelligent, successful people in the world want world peace, but most of them believe peace will never be attained. The educated classes in general have read more on the history of war than the uneducated. As a result, the educated tend to be more pessimistic about the prospects of building a durable peace.

Where should we start when the problem of ending war and building peace appears close to impossible? The solution to war and these other problems involves learning how to apply the same success formula that built the then seemingly unbuildable Golden Gate Bridge to also build a seemingly unbuildable world peace.

To build a workable bridge we apply the methods of science to understand the laws of physical action. In a like manner to build a workable peace we apply the methods of science to understand the laws of human action. Here then is a major solution and we’re only in the second lecture. It has to do with our method. It’s all in the method. It has to do with our method of solving social problems, or human-caused problems.

The method of approach to a correct understanding of the causes of both physical actions and human actions is one and the same, namely the scientific method. This method is a practical approach. We apply it to identify the causes of things. And so in the physical sciences we apply the scientific method to identify the causes of physical action phenomena. In human action or social science, we apply the scientific method to identify the causes of human action phenomena.

One of the aims of this seminar is to show you how to apply the science of human action to identify the causes of the human action effects that you both like and dislike. That’s what you’re the most interested in, the things you like and dislike the most.

As we continue, you can observe for yourself that the major social problems of our time continue for one reason. It is this: most educated, intelligent, and successful adults continue to mislabel the causes of these problems. The effects are less than desirable. When we mislabel the causes of war, poverty, inflation, depression; these unwanted social effects will plague us without remission, without let up.

Human success in every endeavor depends upon the correct identification of causality. All mislabeling will affect you directly or indirectly. What if we mislabel the causes of financial success, which you want, career success, which you want, marital success which you want, parenting success which you want, academic success, entrepreneurial success, all of which you want? What if you mislabel the causes of all of these?

If we cannot correctly identify the causes of all of these desirable goals, we will encounter great difficulty in attaining any of them. The main focus of the science of human action and optimization theory is to identify causality. What are the causes behind the success or failure of the individual to attain specific goals as well as an entire nation of individuals to attain their common goals?

Whenever anyone improves his understanding of causality, he has gained a benefit of immense value. It is a benefit and a value that will never wear out but it also is a difficult benefit to market. You can’t market the benefit by saying, “Ladies and gentlemen, we are here to sell you on the greatest benefit of all, a better understanding of causality.” If you tell them that, there will be no pushing and shoving to join your seminar. In fact, hardly anyone will be there at all if you tell them that. There is almost no demand for this intangible benefit. There is almost no demand for the most important benefit you could ever realize in your entire life. Almost nobody wants this. That includes all your friends and your business associates and your relatives.

Has a friend or associate ever told you, “You know, Frank, my problem is, I don’t know what the hell is going on. You know, what I really need is a better understanding of the causes of things.” And you say, “Well, the causes of what things? What are you talking about?”

Then your friend says, “Well, I need an understanding of the causes of things, you know, effects, the causes of the effects, the things I like and really dislike. That’s what I need to understand better, what causes all this?” Who has ever said this?

What are your friends and associates most likely to tell you? What do I need? He needs the perceived benefits. You know, what I really need is a new car. A Lexus or a Rolls would be nice. I need a new car, for my image, or whatever. I need a new wardrobe, a whole new Brooks Brothers collection of suits and so forth. Or I need a new job or I need a new career or I really need a vacation in Paris or you know I really need a new relationship with someone in Paris.

Is that what you’re most likely to hear? The benefits to be gained from improving our understanding of the causes and effects of things are largely hidden from view, as are the causes of the things we most like and dislike also hidden from view. The method we will apply to improve our understanding of causality is the most advanced method, the most successful method, the most remarkable method, the most practical method ever invented, namely, the scientific method.

As you will see, this is not an overstatement. I’m now going to show you the range of knowledge to which we will apply this scientific method of understanding in the lectures ahead. The main title, as you know, is Principles of Human Action. It doesn’t tell you much about the content. Therefore, I will give you the subtitle, which we haven’t given you in our literature. The subtitle is: Science and Theory on the Optimization of Prosperity, Progress, Peace, and Freedom.

Now the shortened name for the science is simply optimization theory. It is an optimization theory on prosperity, progress, peace, and freedom. Now one of the problems we have in building a science is that no two people ever assign the exact same meaning to any word they use in common and therefore, to build a science at least some of the basic terms must be defined.

The word optimize, of course, is in your vocabulary. It is in mine. But you do not know precisely what I mean by the term optimize. That is true of all of you until I do what? Until I define what it means, for me at least. Optimization is the act of obtaining the greatest degree or best result possible. And so I have given you the subtitle, I will now give you the sub-sub title, in nine parts. That’s what we are going to do during these lectures.

I will begin with the first sub-sub title: Science on the Optimization of Prosperity and the Attenuation of Poverty. Now the term attenuation is commonly used in science and many of you are familiar with this word, especially if you have a background in science. Again, to communicate, even though attenuation is in your vocabulary you still don’t know what I mean by it. This is the key term. You must know what I mean by it if we are talking about the same thing. Fair enough?

Attenuation is the act of making something weaker in effect or reducing its intensity, from the Latin attenuāre. Its definition is to make thin or reduce. When you turn down the volume control, for example, or loudness control on your sound system, what are you doing? You are attenuating what? The sound waves. As you continue attenuating the volume of the sound, the sound gets what? Weaker and weaker until it is what? Inaudible. You’ve all done this, right? All of you have done this?

On some audio preamplifiers, what is commonly called the volume control or the loudness control is called the attenuator. That’s part of the snob appeal if you paid $2,000 dollars for your amplifier with no preamp – that is just $2,000 dollars for the home amplifier. It will probably say attenuator. That is a part of that $2,000 dollars.

In this optimization theory I am going to show you how to weaken in intensity, that is to attenuate, the undesirable effect known as poverty while at the same time attaining to the greatest degree possible, that is optimize, the effect known as prosperity.

Continuing then with the sub-sub titles…

Science on the Optimization of Peace and the Attenuation of War.

Science on the optimization of progressive action and the attenuation of regressive action.

Science on the optimization of economic growth and the attenuation of economic depression.

Science on the optimization of monetary security and the attenuation of monetary inflation.

Science on the optimization of urban security and the attenuation of urban crime.

Science on the optimization of education and the attenuation of indoctrination.

Science on the optimization of freedom and the attenuation of servitude and the role of the individual, that’s you, in the application of these sciences for its immediate benefit and the consequent enrichment of society.

Now this means that you can benefit from the knowledge of this science now, right now you can benefit. And as a consequence, the rest of society will benefit later. You get it first, they will get it later. That’s only fair. You are paying and they’re not.

Drama is in your vocabulary, right? All of you enjoy a good drama, right? If I can show you the drama and the excitement that comes from increasing your understanding of causality, if I can do that, then I can entertain you. To entertain is to gain the attention of someone’s mind in an enjoyable way.

But to successfully entertain educated, intelligent, successful adults you have to remove the barriers to entertainment. When the subject concerns the discovery of super solutions to super problems, then the problem is: how can you get the attention of even one single person?

The dominant attitude of most Americans towards the world’s super problems is largely one of indifference. To observe that people are indifferent is not the same as to blame them for being indifferent. People have a reason to be indifferent about super problems such as war, poverty, and servitude. Here’s your first example of a principle concerning human action, here’s one aspect of what it means to be human.

The principle explains why people are indifferent about the super problems and that is you only act when you believe your actions will change future conditions. To illustrate, let’s say it is 6:30 in the morning and you are in the middle of your two-mile jog. Suddenly half a block ahead you see a house with black smoke pouring out of the second story window. The street is deserted. You pick up your speed and arrive at the house panting and out of breath.

Picture this: it’s just you and the burning house. What will you do? Do you know? First of all, not one of you in this room would be indifferent or apathetic about the fire. You might attempt to alert anyone who might be asleep in the house. It is 6:30 in the morning. Could someone still be asleep? A lot of somebody’s could, right?

You might pound on a neighbor’s door for help. You might call 911 on your cell phone that you take with you when you jog in case there is ever a fire that you have to alert someone about. One thing is certain. You would not jog on by thinking well, it’s not my problem and I am timing my jog and I’ve got to complete this under a certain time.

There would be no indifference on your part. You would take immediate action. You would make it your problem. I claim all of you would do this. Does anyone want to challenge that? You would do it. I claim you would. You might even run into the burning house to rescue the screaming child that you see pounding on the glass on the inside of the front window.

Would that get your attention? A five-year-old boy pounding on the window and the house is in flames. Or, would you think, well, I am sorry about this, but I am tracking the time here on my jog. Without hesitation, you would take action, decisive action, because why? Why would all of you take action? Do all of you know why before I say it? All of you would take action because you believe it is possible for your actions to make a difference, am I right? To save a life, to save the structure, to save the day.

You act, when? When you believe your actions can change future conditions. Well, let’s return to one of the subjects of the seminar, science on the optimization of peace and the attenuation of war. How many of your fellow Americans believe they can take an action that could bring about world peace? The number is small. Most people perceive the problem of ending war and establishing peace to be either unsolvable or at least beyond their potential to solve.

Well, as long as they believe their actions cannot change future conditions, what does this mean? They will not what? Act. And yet the same people would act to save a stranger’s house from fire if they thought their actions would count. And in a like manner they would act to end war and attain peace if they believe their actions will count.

The potential for an outbreak of high technology war still threatens to destroy nearly every house in the nation. Those who act to save a single house would also act to save all of the houses in the nation if one thing – if they thought their actions would count.

Continuing with another sub-sub title. Science on the optimization of monetary security and the attenuation of monetary inflation.

You know, inflation is another problem perceived to be so large the individual is unable to combat it. When inflation heats up, it seems the best the individual can do is to convert his paper currency into tangible assets. In this he may find some short-term protection, but the history of world inflation has taught us that inflation becomes a major cause of business failure. Where business fails and the production of goods falls, consumption of goods must also fall. Tangible assets such as gold lose their glitter when there are few products to buy. When an ounce of your gold will only buy, let’s say, a bar and a half of soap, which is in short supply, what’s your gold worth? A bar of gold will buy a bar and a half of soap or even two bars of soap. What’s your gold worth?

In a later session I will discuss an alternative to monetary inflation. Another sub-sub title: Science on the optimization of urban security and the attenuation of urban crime.

The national and local crime reports remind us that the incidence of burglary, robbery, assault, arson, and theft continue to both spread and increase.

Some people have organized neighborhood watch groups. Others have turned their homes into armed fortresses. But if you have to stay home to guard your family and your castle, I presume you do recognize the quality of your life has suffered sharply, has it not? You get to stay home to guard your castle. Can’t leave tonight, can’t go to the theater, can’t go for a picnic, can’t take a vacation, got to guard the castle. That’s a big negative impact on the quality of your life. In a later session I will discuss a practical approach to the reduction of urban crime.

Another sub-sub title: Science on the optimization of education and the attenuation of indoctrination.

From the time of our youth, all of us have been indoctrinated with various doctrines. Few of us consciously accept any of these doctrines. At the same time they become a part of our most fundamental premises and beliefs.

By the time we are adults, these fundamental premises and beliefs are protected from challenge and attack by what I call what? By your ideological immune system. For an institution of learning to go beyond the mere indoctrination of students and enter the realm of education, we must address this question – it is one of the central questions we will deal with in these lectures. It is this: how can you measure the quality of doctrines?

When the subject is education, you can’t ask a more important question than this. The very question itself implies that some doctrines must be high quality and other doctrines must be low quality. If that’s true, then how do you tell the difference? Write me an essay, turn it in next week. That is just a rhetorical essay. You don’t have to do it.

At this point it should come as no surprise that I am going to apply the methods of science to show you the difference. When you can measure the difference, you will gain the use of an extremely valuable tool. One of my aims is to show you how to master, ladies and gentlemen, a science on the qualitative analysis of doctrines.

To accomplish this we must break away from the traditional approach to education that all of you went through. Historically, education has been an exercise in indoctrinating people with doctrines. How can you and I depart from this indoctrination procedure? How can we do this? Here will be the approach.

As we go through the lectures, I will ask you to direct your attention to certain observable principles. I will ask you, sir, can you observe the consistent operation of this particular principle? Madam, can you observe the operation of this principle independently of anything I have to say about it?

If your answer is yes, then the reason to accept that the principle is true is not because I claim it’s true. The reason to accept it as true is because you have independently experienced it to be true. And if I am showing you a concept that none of us can directly observe, let’s say it requires pure reason to understand, then you apply your own reason. And when you are independently convinced that it is reasonable, then accept it as true, in that order.

The focus will be on a scientific approach to your acquisition of a wealth of useful knowledge. This approach will enable us to move together beyond the limits of mere indoctrination. I believe you will find that education without indoctrination is an entertaining, challenging, and rewarding experience.

Here’s another sub-sub title: Science on the Optimization of Prosperity and the Attenuation of Poverty, according to the World Bank.

They tell us, in this world development report of 1990, that in the developing nations 1.1 billion people are classified as poor with annual incomes of $730 dollars or less. Of this 1.1 billion called poor, two-thirds of these, 633 million, were classed as extremely poor with annual incomes below $275 dollars. Now this was only the number of ‘poor’ in the so-called developing nations.

Here we have another problem of seemingly overwhelming dimension. And yet this problem of crippling poverty will go away not by itself, but when we apply just two things. Just two things will make it go away. The first is more science and the second is better science. We have a misunderstanding of an essential principle, which I will identify later today, the principle of prosperity. Even in America where, for more than a century, we have attained one of the world’s greatest concentrations of prosperity. But there has never been a prosperity revolution in America.

Later I will begin explaining how the principle of prosperity can be applied toward the optimization of prosperity and the attenuation of poverty.

Finally, we have this sub-sub title: Science and the Optimization of Freedom and the Attenuation of Servitude.

The problem of involuntary servitude, bonded slavery, still exists throughout the world.

In those nations where individuals have a large measure of freedom to come and go as they please and to control their own lives, there is a general apathy toward the importance of guarding against the erosion of their freedom. Well, here is an explanation for this general indifference. When an individual possesses freedom, it is almost inconceivable to him that his freedom could ever be lost. And so throughout history there is only one certain means of gaining an individual’s attention on the importance of guarding his freedom. Just one way to get it. Take it away.

The people on the screen have lost their freedom. You can see for example the barbed wire that confines them to what is called a concentration camp. When these people lost their freedom, do you know what they gained? They gained their slavery, their servitude proving that an unwanted gain can, of course, be a loss.

A concentration camp is a camp where slave masters concentrate their slaves, which makes it a slave camp. These slaves have this in common: the guards with the guns. Right here, that’s a gun. The guards with the guns have the attention of all of these people now on what subject? The importance of freedom. But their newfound interest in freedom has come too late. If they try to regain their freedom by escaping, it means almost certain death or worse.

Did these people who were once free make some serious mistake that cost them their freedom or were they merely the victims of circumstance? What do you think? In a later session I will return to this optimization, a problem of how we can optimize freedom and attenuate servitude.

Through no fault of your own, you were born at a time when the social crisis has gone far beyond anything our ancestors experienced. There is nothing to be gained, however, by criticizing those who would rather not think about it, which is almost everybody. But it’s a mistake for everyone to ignore the reality of this. The industrial nations have in place, and fully operational, three technologies that, if launched, can bring about our extinction: biological warfare, chemical warfare, and atomic warfare.

The old approaches to ending this social crisis have failed. They failed because the causes of the crisis have been hidden from view. And if the causes of something we dislike have been hidden from view, this does not mean they must remain hidden forever. The best method yet developed to reveal the hidden causes of the effects we like and dislike is the scientific method. By applying this method, we can arrive at new understandings of causality.

Graphically, the solution I gave you earlier looks like this. The aim of this seminar, Principles of Human Action, is to give you a rapid acceleration of your correct understanding of the causes of human action effects. This acceleration of your understanding of causality will take place during the some thirty hours in which this seminar is presented.

The name I give for this rapid acceleration of understanding is an accelerated intellectual evolution.

I’d like to discuss your perception of the speed with which I disclosed this optimization theory as science, that is, your perception of how it’s going. Your perception can be one of three. One, the presentation is going too slow. Two, the presentation is going too fast. Three, the presentation is going neither too slow nor too fast. That covers all possibilities with regard to my delivery.

Now, at this point, some of you might think the lectures are going just too slow. Why doesn’t he get on with it? Let’s speed it up. Why don’t you put the lecture on fast forward? Somebody might say, I’m not only keeping up with you, I’m way ahead of you and I’ve had many people tell me this after the first or second break. Put it on fast-forward because I’m ahead of you.

On the other hand, some people may think the lectures are going too fast. Why doesn’t he slow it down? I can’t write this fast. I can’t think this quickly. Slow down, you’re ahead of me.

And some of you will think, well, the lectures are going neither too slow nor too fast. They’re just about right.

Ladies and gentlemen, first of all this is a university-level seminar, a graduate-level seminar if you will, a university-level graduate seminar. But unlike a university seminar, we have a much more heterogeneous selection of students. It’s heterogeneous relative to age, education, and occupation. Seminar enrollees may range in age from 18 to over 65. They may be high school graduates, college graduates, they may have various advanced degrees, with doctor as a title. They may be mothers with an 18 hours to 24 hours a day job of just raising children. They may be businessmen, accountants, dentists, students, engineers, physicians, proprietors, clerks, or what have you.

Every one of you in this room has a unique combination of experiences and genetic predispositions. For this and other reasons, each of you will have a different response to the rate of disclosure. Nevertheless, here is only part of what we’re going to show you how to do in 30 hours of lecture.

If prosperity is preferable to poverty, then how can we optimize prosperity? If progress is preferable to regress, how can we optimize progress? If peace is preferable to war, how can we optimize peace? And if freedom is preferable to servitude, how can we optimize freedom? These questions presume all four of these desirable aims can be optimized in the real world. I will demonstrate that, by applying workable principles, we can optimize prosperity, progress, peace, and freedom.

If I can deliver on this promise in 30 hours, that means you cannot afford to miss any of the lectures. If I can deliver on this promise, you can’t afford to miss a session. If I can’t deliver, it doesn’t matter, and we will give you your money back. If I can deliver on this promise, it means, from my view, you’ve gotten the best bargain in education available anywhere. Anywhere.

If I can’t deliver, it’s no bargain, it’s no value. You wasted your time if I cannot deliver. You wasted your time, but we will give you your money back. I can’t give you your time back. The guarantee you’ve seen, all of you have read the guarantee on our literature, but here it is. It’s not one I think you’ve ever gotten from anybody before and I’m mentioning it now, knowing that all of you are enrolled in the seminar.

If, in your own judgment, the time and tuition that you have invested in the Principles of Human Action seminar could have been more profitably invested in any other available alternative, such as a family affair, some important business venture you’re involved in, your profession, you’ve got to burn the midnight oil, your work, recreation, you want to go skiing, or some educational alternative, you’re going to take some advanced course at the UCLA, or USC, or what have you.

Then, after the fact, after you’ve completed this seminar, in reflection, if you think, you know, I should have done something else instead of taking this damn seminar, simply let us know and we will write you a check for the full amount of the tuition and the check will not bounce. Did you ever get an offer like that? Many of you here have spent 12 years in school, 15 years in school, 18 years in school, 20 years in school. Did you ever get any guarantee like that from any of your professors? You have to have a lot of confidence in the quality and value of your product to guarantee it.

Now I cannot control all the factors that go into the guarantee on the value that you will get from this seminar because value, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. For you to gain value I first have to get your attention and not just for a few minutes or even for a few hours, but I have to get your attention for 30 hours. This is not easy to do and this will take some doing on my part and on yours. Perhaps, when the subject of discussion is abstractions, it turns out that you have a short attention span.

This seminar is about a prime subject: principles. Not all principles. It focuses on principles of human action, which is the name of the seminar.

In contrast, the principles of physical action are for courses in physics. The principles of biological action are for courses in biology. All principles, as you know, are intangible abstractions and to understand a principle you need a long attention span – no exceptions. By long attention span I mean you can concentrate on a discussion of serious ideas for an hour or more at a time.

Now, many people can concentrate for an hour while they’re reading, let’s say, a romance novel. How many of you have read the recent best-seller by Robert J. Waller called The Bridges of Madison County? Let me see a show of hands. Okay, is that the same half that raised their hands before, who had answered the questions? Or, are these different hands? It looks like over a third of you have read this book. This little book has sold millions of copies. If you’ve read the book you will most likely be able to sit through the three-hour movie. It will soon be made into a Hollywood extravaganza starring none other than Clint Eastwood as the romantic photographer, and the delightful Meryl Streep as his swept-off-her-feet heroine and lover.

Now, I’m sure you can concentrate for hours at a time, for example, on a romance novel or an adventure novel, if the adventure novel is compelling enough. You can read this for hours, am I right? Or if you’re a sportsman. Is there anyone here wanting to admit ‘I’m a sportsman?’ Okay, there are a dozen people who are sportsmen. You can concentrate on improving your golf swing, especially focusing on how to get out of the sand trap or out of the rough for hours at a time. You’ll go out there blasting away for hours, am I right? Same damn stroke, same sand pile, same rough for hours and hours.

How many tennis players are there? Okay, any good tennis player can concentrate for hours at a time on improving the effectiveness of his or her second serve by increasing its power, adding more slice, and bettering the position. Hours and hours you’ll be out there on the second serve. Not the first serve. There’s another whole regimen on the first serve because they’re different. It’s a whole different thing. There are many others who can concentrate for hours at a time on such things as flying an airplane or learning to use the latest piece of software.

But – and here is the big question – can you concentrate on a discussion of ideas, principles and abstractions, not a single tangible thing at all, for hours at a time? Most people cannot do this. Probably most of the people you know cannot do this. Of course the question I have is: can you do this? Because if you can’t do it, you won’t get much of anything out of this seminar.

If you can’t concentrate on abstractions for hours at a time, there is another thing you won’t ever get. I will define it later. It’s called education. If you cannot concentrate on abstractions, you are uneducable; you cannot be educated. I’ll prove this later. Most people confuse education with training. Twentieth century American schools are mainly in the training business. Hardly any American college graduates get an education. They get trained.

One reason students are more likely to get trained is that it is a lot easier to train a student than it is to educate a student. Education is difficult because it requires understanding. It is tough. As a teacher you must understand that a student has got to be able to understand abstractions in the form of principles, laws, concepts, and ideas. And most importantly, education involves understanding causality.

Training is easy because you don’t have to understand anything to be trained. You don’t have to think to be trained. You don’t have to think to be indoctrinated. To be trained you merely have to imitate, duplicate, and replicate. You learn by rote. You follow the instructions. And most importantly on examination day, you tell the teacher what the teacher wants to hear.

Those who do the best job of telling a teacher what the teacher wants to hear get the best grades. Those who fail to tell the teacher what the teacher wants to hear either get poor grades or they flunk. And so modern educators take great pride in calling this education. It’s not; it’s training. And all training by its very nature is a derivative of indoctrination. All training involves indoctrination. Two classes of adults are offended by this statement. You can guess who they are: teachers who are trainers and indoctrinators, but who think they are educators; the former students are offended who have merely been trained and indoctrinated but who think they are educated.

Training has value, and trained people can be useful members of society, but you are in big trouble if you think you have been educated when you have merely been trained. At one time adults in general had longer attention spans for serious things but most of those adults are now dead. They’re almost all dead.

We live in the era of mass communication, which means masses of communiques bombarding you from all directions. Radio, if not television, was in full bloom when you were born. This is the age of the sound bite, ten or twenty seconds of information before the next commercial or the next topic. But do not worry, if you’ve made it through these first two lectures you will do all right in the remaining eighteen. You are two-twentieths of the way through the seminar. And if you haven’t quite made it, I won’t ask for a show of hands, and you’re not quite sure what you’re doing here and what all of this has got to do with you, that’s okay, too. You can still be doing okay.

If you hang in there, as they say, your reward, I promise you, will be very large. I’ll give you a final preview of coming attractions. My aim is to give you something that is quite valuable. But if I had told you in advance this is one of the things you are going to get, it would be nearly impossible to get you to join this seminar. If I tell you what’s in the seminar, I can’t get anybody to come. It’s true!

A student, who is responsible for perhaps a third of the people in the room, will tell you the difficulty. He’s always saying, “Snelson, you tell them too much. We have to downplay the magnitude of this seminar and what it encompasses.” And he’s probably right and he is very influential in this regard. Well, what could be so valuable and yet most people wouldn’t want it if you told them they were going to get it?

The term for what I hope to give you was coined by a professor of philosophy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Thomas S. Kuhn, who wrote a most influential work. His book was called The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, published in 1960. It was Professor Kuhn at MIT who coined and popularized the now-familiar term, ‘paradigm shift’ in explaining the role of the paradigm shift as the driving force behind all scientific revolutions.

The word, paradigm, has enjoyed English usage since the 15th century. Its roots are Latin. The Latin, ‘paradigma,’ referred to a pattern, a pattern created by setting an array of things side by side. This creates a pattern. The word means a pattern or model of how things work or how they ought to work. And so your social paradigm is your worldview, your ideal model of how you think society works or at least ought to work. There is not anything in your thinking much more fundamental than your social paradigm, which makes up an essential part of your entire belief system.

Well, one aim here is to change your social paradigm so that you achieve a paradigm shift, to use Professor Kuhn’s term. But a paradigm shift from what paradigm to what other paradigm? You will soon find out if you’re going to be here for the rest of the sessions. For all of you, this shift to a new paradigm will not come easy because all of you have an ideological immune system, which will protect you from, first and foremost above anything else, the acceptance of a new paradigm.

However, if you can make this paradigm shift, it won’t hurt you any more than your predecessors were hurt when they shifted from the unscientific paradigm that yellow fever and malaria are caused by moral decadence, which was one explanation, or unsanitary living conditions, to the scientific paradigm that yellow fever is caused by the bite of an infected aedes aegypti mosquito. With a new paradigm it became clear that decadence and sanitation had nothing to do with causing yellow fever and malaria. The biological paradigm shift on the transmission of yellow fever and malaria has saved millions of lives. The sociological paradigm shift that this seminar fosters can save billions of lives. In fact, I am inviting you to play a role in saving billions of lives.

I hope you are not asking, “Yeah, but what’s in it for me?” This point, to believe you can play such a role, will take a paradigm shift.

Add comment