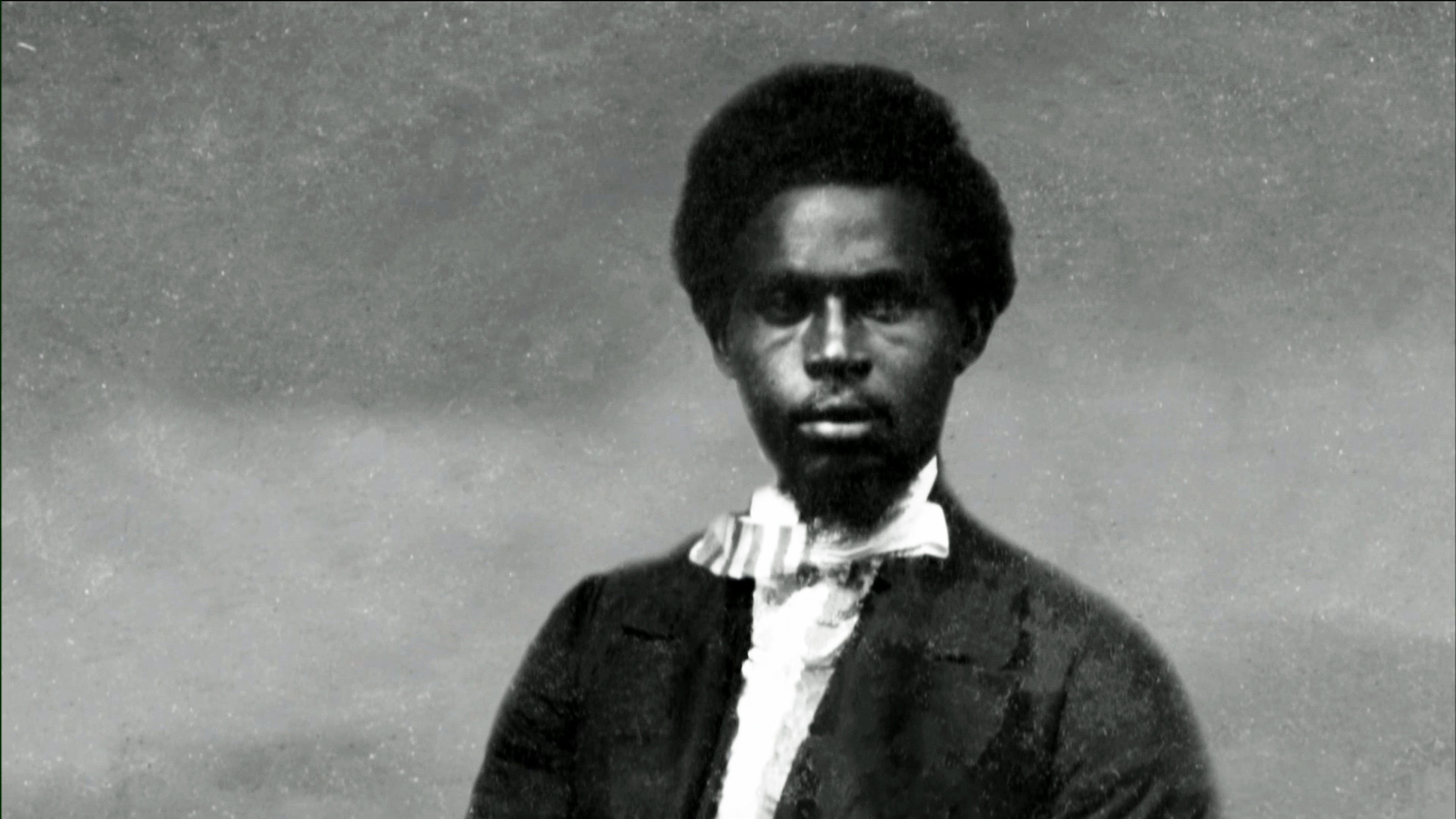

Fight for Freedom: The Legendary Life of Robert Smalls

Throughout the millennia, humans have fought for sovereignty, liberty, and self-determination to live the life they see fit for themselves. From civil rights activists, to freedom fighters combating dictatorial regimes, to local farmers taking up arms against an occupying force, people acted against adversity and entities which wished to dictate how they should behave, speak, and experience life. There are countless tales of such endeavors, but this one in particular could have come straight out of a Jules Verne novel or a Hollywood action film: Robert Smalls, from Charleston slave to United States congressman.

Smalls was born in 1839 in Beaufort, SC to Lydia Polite, a slave to Henry McKee. He worked as a servant in the McKee house for all of his childhood and preteen years. At the age of 12, he was sent to work as a dock laborer in Charleston by McKee in order to send funds back to the master’s house. Of the sixteen dollars he made a week as a laborer, he was allowed to keep one. Working his way up to a wheelman of sailing vessels, Smalls became familiar with the Charleston waters, an experience which would eventually change his life, and those he cared about, for the better.

At the age of 17, Robert Smalls married Hannah Jones, slave and single mother of two. They had a daughter together in 1858, and a son in 1861, who died shortly thereafter. Smalls worked to purchase his family’s freedom, but could only muster $100 of the $800 asking price (about $24,127 in today’s currency).

Shortly after the Civil War erupted in April of 1861 with the Battle of Fort Sumter, Smalls was commanded to wheel the CSS Planter—a Confederate vessel ordered to survey waterways, lay mines, and deliver dispatches and supplies. As Charleston was a major port town, Smalls and others could witness the Union blockade mounting on the outer banks; he was so close to freedom, yet was firmly ensnared in the workings of a state which didn’t see him as an equal, let alone a person. Robert Smalls decided to act.

On May 12, 1862, the Planter was docked as the crew and laborers unloaded munitions. Smalls asked the captain if the families of the crew could visit before they departed once more. The captain allowed the request, but stated that civilians must leave before curfew. Smalls sent word and the families arrived, at which time he made known his plan. Some of the family members were justifiably hesitant, fearing capture or worse. Hannah Jones looked to her husband and replied: “It is a risk, dear, but you and I, and our little ones must be free. I will go, for where you die, I will die.”

Early in the morning on May 13th, Smalls and the enslaved crew feigned departure with their families, hiding them in a wharf down the harbor while the rest made preparations to flee. Smalls disguised himself in a captain’s uniform and set sail down the harbor to pick up the families along the way. Smalls and the crew had to sail past Fort Sumter—now in Confederate hands. The disguises worked, and the CSS Planter commandeered by escaped slaves sailed out of the harbor and into the Union blockade, raising a white bed sheet as a flag to indicate no harm. A witness aboard the USS Onward noted that upon approaching the Planter with hesitation, Robert Smalls greeted the Union crew and said: “Good morning, sir! I’ve brought you some of the old United States guns, sir!” Robert Smalls saved the lives of his crewmates and their families, evaded Confederate patrols and Fort Sumter, and ‘returned’ crucial military arms and munitions—at the age of 23.

Smalls’ heroic exploits traveled far and wide throughout the North. Though he wasn’t a graduate of the Naval Academy and couldn’t hold rank, he went on to pilot the now USS Planter, as well as other Union vessels such as the USS Keokuk, USS Crusader, and the USS Isaac Smith. He supported Union expeditions into Southern territory, and was witness to fighting such as the Second Battle of Pocotaligo, an attack on Fort Sumter, and even aided in General Sherman’s movement through Savannah, GA.

Following the culmination of the war, Smalls returned to his hometown and bought the very house he was enslaved in. He would go on to purchase a two-story building in Beaumont and transform it into a a school for children of former slaves. Smalls had a penchant for charity, entrepreneurship, and giving back to his community; this shined throughout the war when he supported an effort to raise funds for African Americans and those formerly enslaved, known as the Port Royal Experiment. Smalls would go on to form partnerships with other freedmen like Richard Gleaves and open up shops for the needs of former enslaved people. In 1872, Smalls published the Beaufort Southern Standard newspaper.

With Congress’ overriding of President Andrew Johnson’s post-war vetoes, the Radical Republicans were able to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Shortly thereafter in 1868, the 14th Amendment was ratified by the states, finally extending full citizenship to all Americans, regardless of race. This greatly benefited Reconstruction efforts and black-owned businesses which were previously prevented from growing and expanding throughout the South. The post-war political landscape was very tense; the Democratic Party opposed civil rights and would consistently vote against measures acknowledging equal treatment of non-white Americans.

Robert Smalls would win various political positions including a delegate seat at the 1868 South Carolina Constitutional Convention, where he fought for free schooling for all South Carolinian children. During his tenure in the South Carolina House of Representatives, Smalls argued for the Homestead Act and a civil rights bill. Smalls would later be elected to the State Senate in 1872, where he was considered a formidable debater and proponent of broader civil rights legislation. Though Smalls was appointed to many more positions in his lifetime, these are important to note for his dedication towards expanding civil rights to all Americans, and to provide equal opportunity to South Carolinian children regardless of background, race, or class.

Smalls would go on to serve two terms (1875-1879) in the United States House of Representatives for South Carolina’s 5th district, and later as a Representative for the 7th district (1884-1887). After Joseph Rainey, he was the second-longest serving African American member of Congress up until the mid-20th century—a considerable accomplishment considering the adversity and tension experienced in the years of Reconstruction.

Smalls was defeated in 1878 and in 1880 for the House seat by southern Democrat George D. Tillman, but succeeded in regaining his seat in 1882. Smalls continuously fought against gradual disenfranchisement towards blacks in the South. During the 1895 South Carolina Constitutional Convention, Smalls and other black politicians stood firm against the Democrat-controlled legislature which sought to return to a sort of pre-war civil rights structure by amending the state constitution. Unfortunately, the legislature prevailed, and similar constitutions were adopted throughout the South by like-minded legislative bodies. These amendments would give way to what would later be known as the Jim Crow South.

Robert Smalls’ life could be something out of a fable grandparents tell in order to bestow lessons of honor, perseverance, and responsibility to younger generations. Having been born into one of the toughest times for African Americans, Robert Smalls defied odds and resisted the inhuman commands of his oppressors, fought for the abolition of slavery, and advocated for equal treatment of all Americans under the law. Who’s to know how Reconstruction efforts in South Carolina would have developed without the passion and advocacy of individuals like Robert Smalls. In the face of the biggest odds imaginable, from everyday discrimination, to systemic injustice, to political sabotage, Robert Smalls helped to form a new American class: one which learns from the past and looks to the future; one which would fight for equal treatment, opportunity, and respect for all. Let us remember Robert Smalls for the man he was, and his mission to better this country, for the good of its people, and the future of its children.

Free the People publishes opinion-based articles from contributing writers. The opinions and ideas expressed do not always reflect the opinions and ideas that Free the People endorses. We believe in free speech, and in providing a platform for open dialogue. Feel free to leave a comment.

Chris Partridge

Great piece Connor. Very well written and informative.