Lecture #9, Doctrines and Free Trade

Human Action Principles

March 5th, 1995

Lecture Number Nine

I will begin this session with a question I posed earlier: How can we build a science on the qualitative analysis of doctrines? I will answer this question in part with a second question, namely, how can we differentiate between a high-quality doctrine versus a low-quality doctrine? Are all doctrines of equal quality, or are there some doctrines that are of higher quality than others?

How can we make such a differentiation? How can such a differentiation ever be more than, let’s say, A’s opinion versus B’s opinion? If we’re going to approach this difficult problem from a scientific perspective, there are certain things we are required to do.

One of them is, we have to present some fundamental definitions upon which our science on the qualitative analysis of doctrines can be built. Therefore, a rational place to start would be to actually define two essential terms, namely, high-quality doctrine and low-quality doctrine.

Now, please note, I have not said we are going to differentiate between a good doctrine versus a bad doctrine or a right doctrine versus a wrong doctrine. Our simplex or singular concern will be with the identification of a high-quality doctrine versus a low-quality doctrine. In order for you to understand what I’m talking about in this regard, I must define these terms.

A high-quality doctrine presents a verifiable explanation of causality and promulgates true means that are successful in the attainment of its stated goals. Once we have defined the nature of a high-quality doctrine, it’s easy to define its opposite, the low-quality doctrine. A low-quality doctrine presents unverifiable explanations of causality and promulgates false means that are unsuccessful in the attainment of its stated goals.

Now that we have defined these terms, we have a basis for the differentiation between high-quality versus low-quality doctrine. I will start by analyzing a popular doctrine accepted by the majority of educated, intelligent, and successful people. This doctrine has enjoyed great popularity during the past 400 years. I’m going to identify this doctrine, but my description and the language that I will use would be language unfamiliar to most of the people who have believed in this doctrine.

We’re going to talk about the doctrine of special privilege. That involves government-imposed special privilege for a special few. The belief is, this will bring about the greatest good for the greatest number. A historical example of an application of the doctrine of special privilege involved a political/economic system known as mercantilism.

This was the system of special privilege that prevailed in the Western world during the 17th and 18th centuries. The advocates of this social system of mercantilism claimed that in order for our nation to become wealthy, we must export the largest number of products possible and import the smallest number of products possible.

To bring about wealth for the nation, in other words, the government must use force to restrict or prevent the importation of foreign-made products. The government must impose a strict regulation on the entire national economy. The government must provide certain favored domestic producers with special privilege. The special privilege; domestic producers must be protected from foreign producers who manufacture.

Most importantly, we must be protected from those who manufacture higher-quality products at lower prices. This is to be feared. Anyone who can manufacture a higher-quality product at a lower price is to be feared. If we can prevent the people from purchasing these higher-quality, lower-priced products made by foreigners, then our people will be prosperous, and our nation will be wealthy and flourish. That’s the argument.

Freely translated, if the government can cause the people to have a lower standard of living, then our nation will be wealthy. This was the main feature of the mercantile doctrine of special privilege for a special few.

In the same year that the American Revolution was launched with the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, in Europe, an even greater revolution was launched. What could be greater than the American Revolution? Well, it was launched by a then-obscure professor of philosophy at the University of Glasgow in Scotland. It’s a name you’ve heard, Professor Adam Smith.

His book has been one of the most influential and revolutionary books ever published. Each time I present this seminar, I offer 50 cents – through inflation I’ll probably offer a dollar now – to anyone in the seminar for the first time who can give me the title of this book that Professor Adam Smith wrote.

“The Wealth of Nations?”

We have an answer of The Wealth of Nations. Anyone else?

“The Wealth of Nations, The Wealth of Nations.”

The Wealth of Nations twice, and three times. Anyone else? Now, you’re not just copying are you? That was independent, right? You knew that? You didn’t just get it from him. Okay.

Let me rephrase the question. Can anyone give me the complete title of this work? Here’s the complete title. See if you think I like the title. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Now the title makes sense.

STUDENT: May I have a quarter?

SNELSON: Sure you can. Nancy, do you have a quarter? Okay, tell you what, I have a quarter. No, wait a minute. I want you to come up here and get your quarter. It’s right there on the lectern. Thank you.

The reason I did that was, several years ago, there had only been two people who got the complete title correct. One of them (I had offered 50 cents) I was digging down into my pockets. I didn’t have 50 cents at that time. Anyhow, some time later, much later, this person complained that he never got his 50 cents. That’s why I had you come up here now and get the quarter.

All right. I presume you think I like Smith’s title. How many think I like Smith’s title? You bet. Here is an entire book on what subject?

CLASS: Causality.

SNELSON: Not only causality, but what causes a nation to become wealthy? It’s the cause, also, of individual prosperity and the cause of national wealth.

I have this question for you: What would have constituted a wealthy nation in Smith’s time 200 years ago, and what might constitute a wealthy nation today? Well, I’ll answer the question. A wealthy nation is one in which the individual consumers have a wealth of products to consume.

Smith points out that if the goal is to attain a wealthy nation, then the mercantile system of government, interventionism and its establishment of special privilege, is a false means. In The Wealth of Nations, he says, quote, “What is prudence?” And the language is a little archaic, but you can follow the drift, I think.

“What is prudence in the conduct of every private family can scarce be folly in that of a great kingdom. If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry.”

Smith is criticizing the interventionism of the British bureaucracy that gave special privilege to certain British manufacturers and producers at the expense of the British consumers. He goes on to say, “But in the mercantile philosophy,” which he’s criticizing now, mercantilism, “the interest of the consumer is almost constantly sacrificed to that of the producer, and it seems to consider production and not consumption as the ultimate end and object of all industry and commerce.”

In still fewer words, Smith gives us a simplex principle to follow that is a true means to the wealth of nations. In a single sentence, he says, “Consumption is the sole end purpose of all production.”

When we look at this principle today, it almost appears obvious. “Of course consumption is the sole end of all production. How else could it be?” we might say today.

But you will find that most of today’s ideologies and popular doctrines reject this principle. To use the language of this seminar, Smith is saying, hey, if we want to achieve national wealth, if we’re going to attain the greatest prosperity for the greatest number, then the consumer has got to be the boss. That’s in the language of this seminar.

The consumer must have the freedom to choose what products he wants to consume in his quest for greater satisfaction. This means, if the consumer is the boss of production, then the bureaucrat can’t be the boss of production. You can’t have two bosses. It’s one or the other. Furthermore, the bureaucrat can’t favor any producer, manufacturer, or entrepreneur by making them the boss of production by giving them special privilege.

Smith says we must not do this. But where the bureaucrat is the boss, consumption is not the sole end and purpose of all production. Production becomes the end, not consumption. Now, some might say, well, what’s wrong with production becoming the end? Write an essay on that.

Those of you who have been, let’s say, Russia watchers or Soviet watchers while the Soviet Union was in existence over the years have been witness to the result that, during, for example, the Soviet era, government confiscated the people’s freedom to choose. There were no consumer bosses to determine the quantity, quality, and variety of products that were produced in the Soviet Union.

This was a great experiment. We can learn a lot from the Soviet experiment. We’re going to use this experiment to illustrate a lot of points in this seminar. If there are no consumer bosses to make the determination, there’s only one other possibility. The bureaucratic bosses will make this determination.

The effects were vividly described in this Time magazine article on Russia in the February 12, 1965, issue. This article appeared just after Nikita Khrushchev was kicked out of his exalted position as first secretary of the Communist Party and premier of the Soviet Union. And I’ll read this article in part from Time magazine, February 12, 1965.

Quote: “Soviet planning’s faults are chiefly two: too many cooks from the supreme economic council on down and, more often than not, the wrong recipe in 15 copies. Two months ago, a supreme Soviet deputy cited the example of the Izhora factory, which received no fewer than 70 different official instructions from nine state committees, four economic councils, and two state planning committees, all authorized to issue Izhora production orders.”

Wow. “Since factory output goals are either laid down in weight or quota by the planners, a knitwear plant ordered to produce 80,000 caps and sweaters naturally produced only caps. They were smaller and thus cheaper and quicker to make. A factory commanded to make lampshades made them all orange, since sticking to one color kept the assembly line uncomplicated.

“Tire production one year was fixed without checking the plan for motor vehicle output. Taxi drivers were put on a bonus system based on mileage, and soon the Moscow suburbs were full of empty taxis barreling down the boulevards to fatten their bonuses. “No ceiling,” says the sub-headline.

“The tonnage norms particularly piqued Khrushchev’s peasant common sense. Machine builders used eight-inch plates when four-inch plates would easily have done the job. Quote, ‘We make the heaviest machines in the world,’ sighed Nikita. His choice complaint, however, had to do with a Moscow chandelier factory. The more tons of chandeliers the plant produced, the more workers earned the bonuses.”

And his final quote, I will share with you. “The chandeliers grew heavier and heavier until they started pulling the ceilings down. They fulfilled the plan,” admitted Khrushchev angrily, “but who needs this plan? To whom does it give light?” And even though Khrushchev, while serving earlier as Stalin’s chief hatchet man in that role, was one of the exemplary mass murderers of his time.

It was Khrushchev who was in charge of the Great Purge of the 1930s and more, and murdered millions of his own countrymen. In spite of all this, I don’t think we can fault the late Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev, for his sense of humor, which he had. I don’t know. Maybe to murder millions of people you have to have a sense of humor to maintain some sanity.

Since the entire Soviet social system is built upon the doctrine of special privilege, government-imposed special privilege for a special few, in this case Communists, and “all of this will bring about the greatest good for the greatest number.” The Soviets must castigate Adam Smith and his principle that the satisfaction of the consumer boss “is the sole end and purpose of all production.” Adam Smith cannot be welcome in a country like the Soviet Union, because his ideas are 180 degrees out of phase with the ideas of the Communist indoctrinators.

Smith is telling us that the mercantile system of bureaucratic interventionism and special privilege will not cause the wealth of nations; not in England, not in France, not in Russia or any other nation. Finally, Smith says, “The interest of the producer ought to be attended to only so far as it may be necessary for promoting that of the consumer. This maxim is so perfectly self-evident that it would be absurd to attempt to prove it.”

By maxim he means, of course, an expression of general truth. In the language of this seminar, Smith is saying, the fact that the consumer ought to be boss, is a self-evident truth. At this point, I believe Smith committed a serious, major blunder. In fact, it is a reason why his publication of The Wealth of Nations did not have an even larger impact upon the world than it did.

My point is this: The generalization that, in order to optimize the greatest prosperity for the greatest number, the consumer must be the boss, is not a self-evident truth. It must be proven with science. That’s where he made a mistake. It is not self-evident, and if it were self-evident, you wouldn’t have to prove it. The proof will be presented in this seminar.

Nevertheless, the historical impact of Smith’s social revolution was profound. He initiated the first major intellectual assault upon protectionism in which the government-imposed barriers to free trade and the freedom to buy and sell are inflicted upon the marketplace.

This attack upon government interventionism by Smith was profound in support of free trade. That is, Smith has been continued and followed by others. In 1776, when Smith’s An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations was published, David Ricardo was only four years old. Later, Ricardo was, certainly as a young man, strongly influenced by Smith’s book. Smith and Ricardo, Smith being earlier, are considered the two greatest of what are called the classical economists.

David Ricardo completed over a century and a half ago, the intellectual demolition, started by Adam Smith, of all of the arguments in favor of protectionism and interference with free trade. It’s important to note that these classical economists did not start with a preconceived point of view that interference with free trade was bad. They simply showed that government interventionism, in the form of protectionism of special industries and interference with free trade, could not accomplish the goals the government claimed to be seeking in the first place.

In fewer words, the classical economists proved that the means the government interventionists were employing could not attain the ends the government interventionists were seeking. In still fewer words, they were saying, “Hey Jack, it won’t work.”

The classical economists were among the first intellectuals to attack the concept of government-imposed economic interventionism with rational arguments. In doing this, they were literally opposing thousands of years of government interventionism. Economic interventionism was not invented by the British government.

In fact, from the time of the Roman Empire, which extended to the British Isles and to the continent of Europe down to the governments that arose after the collapse of the old empire, one of the major objectives of every government was to impose economic interventionism by force.

How many of you have ever taken a cruise down this beautiful river? It’s the Rhine River. How many of you have cruised the Rhine?

The next time you’re in Germany, it’s well worth cruising the Rhine. It flows for over 800 miles from Switzerland clear up to the North Sea.

One of the main points of interest along the Rhine is all these castles. Here’s one right here. In fact, there was a Hollywood movie, I think, called Castles on the Rhine. How many saw that? Why do you suppose all of these castles were built in the first place? How many think it was to improve tourist travel along the Rhine River?

No. There were two major purposes for these castles. One was to interfere with trade going up the Rhine, and the second was to interfere with trade going down the Rhine. They were commonly used.

If you were a transporter of goods on the river, every time you came to another one of these castles, you get to pay another toll tax. If you refuse to pay, ten soldiers with spears will throw you in the river and confiscate your cargo, and maybe you’ll be lucky and not get speared.

Across the channel, that is, in England, the penalties against those who attempted to engage in free trade were quite severe. During the reign of Edward VI of England, son of the notorious Henry VIII, which you’ve read much about and seen much about, the law explicitly identified what you could not trade in.

For example, you could not trade in any corn growing in the field. Here was one of the castles. Here’s the parapet, and the soldiers were up here guarding the river and so forth, and that was where they defended the river against those who wanted to get by without paying taxes.

“It is forbidden to trade any corn growing in the fields or any other corn or grain, butter, cheese, fish or other dead victuals whatsoever.” What I didn’t tell you when I talked about the Corn Laws is that there were more things beside corn that you were forbidden to trade.

But what if you disobeyed the law and traded in these various commodities anyhow? Smith tells us in his An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, “by the time of Edward VI, it was enacted that whoever should buy any corn or grain with intent to sell it again should be reputed an unlawful engrosser.” Engrosser is an archaic word, essentially, for anyone who was attempting monopolistic control of a product.

The quote continues, “and should, for the first fault, suffer two months imprisonment and forfeit the value of the corn. For the second fault, suffer six months imprisonment and forfeit double the value, and for the third fault be set in the pillory.” And you’ve all seen engravings of people in the town square. Their neck is in this pillory, and that’s when your friends and the people who dislike you can come and pelt you with rocks and what have you and spit at you, whatever. You must be guilty, or why would your head be in the pillory? If you were a good person, you wouldn’t be there.

If this was your third offense for engaging in a free trade, they would lock you up. If there was a third offense beyond the pillory, it said, “and for the third, be set in the pillory, suffering imprisonment during the king’s pleasure.” In other words, you’re going to be imprisoned during the king’s pleasure. How long a term of imprisonment might that be?

Daniel Defoe 1660 to 1731 English novelist and journalist in the pillory at Temple Bar. From The National and Domestic History of England by William Aubrey published London circa 1890

As long as your imprisonment gives the king pleasure, which could be indefinitely, forever. And, in addition to that, you will forfeit all of your goods and chattels. In other words, you’ll forfeit essentially everything you own.

Other than that, what was the penalty? I should remind you that at the time the vermin-infested prisons in those days were a real live nightmare. They were not the country clubs that prisoners have today, at least in the Western world. Now, you don’t want to go into a prison in a third-world country, because they’re about the same as prisons were in England at this time.

Finally, Smith concludes, “The ancient policy of most other parts of Europe was no better than that of England.” In other words, they just did this pretty much all over. Let’s continue to follow Einstein’s advice and see if we can formulate the problem by asking a rational question.

Let’s begin with the premise that I believe all of you will agree with, namely, the wealth of a nation is the summation of the wealth of each individual within the nation. When an individual produces a product that does not exist in nature, then not only is he wealthier, but so is the nation wealthier. If an entrepreneur or manufacturer is producing products, and there are too many products for him and his family to consume, what should he do with the surplus?

The rational thing for him to do might be to find a buyer. Please note, if you find a buyer for your surplus, the purchase will add to the buyer’s wealth. Does everyone see that? So, the true measure of a man’s material wealth is the quantity and quality of products he has acquired, plus the number of new products he has the means to acquire.

And now, the question I’ve been building to, and that is, can any producer of surplus wealth anywhere in the world sell some of his surplus wealth to any willing buyer anywhere in the world without causing harm to any third party anywhere in the world? That’s a critical question. I’m going to devote this entire session to reaching a scientific answer to this question.

In fewer words, can a free market exchange between A and B in any way harm C? And if it does harm C, then the question also arises: How can society protect C? If society decides that A and B ought not to trade with one another, then what should we do if A and B just go ahead and freely trade anyhow? What should we do? Should we follow the leadership of good King Edward VI? Should we confiscate all of A’s and B’s goods? Should we throw them in prison, shoot them if they try to escape to continue their illegal crimes in free trading?

Once we decide that A and B should be denied the freedom to trade, then we must determine what kind of interventionism to employ against them to either get them to stop trading altogether or slow down their trading. The most well-known government mechanism designed to interfere with free trade is called the protective tariff.

For those of you who may not be familiar with the exact nature of tariff, a tariff is a special tax levied upon imported products. We have to examine the effects of the protective tariff. It is important to look at how this tariff tax on imported goods comes into existence. Let’s look again at the law of human action.

All human action involves the employment of a chosen means to achieve the attainment of some perceived greater satisfaction. As I’ve already stated, whenever any consumer boss voluntarily chooses to purchase any product, he is always purchasing the product with the sole aim of attaining some end of greater satisfaction.

This is true for every product that was ever voluntarily purchased. However, historically, all of the entrepreneurs, manufacturers, and proprietors have not always been happy with the idea of the consumers being the boss. Here’s what has happened historically.

Where there is the freedom to buy and sell, the success or failure of every entrepreneur, manufacturer, and proprietor is determined by the purchases of the consumer bosses.

This is one of the truly unique features – don’t ever use that word loosely. Unique means what?

One only and none other. For example, there’s no such thing as the most unique. That’s incorrect. There’s no such thing. This is an important feature of a free market.

Some of these entrepreneurs, manufacturers, proprietors, because of the free market, would like to take away the consumer’s free market vote for the specific reason that the consumers are not voting for them, which means they’re not purchasing their products.

Many of these entrepreneurs and proprietors have not liked this. They say, “I don’t like it when you don’t buy my product.” In fact, many of these entrepreneurs, manufacturers, and proprietors have decided, “Not only do I not like it, I’m the entrepreneur. I’m going to be the boss. Any questions? Good.”

So what do they do? If there’s a free market, how can they be boss? They can’t. If there’s a free market, the entrepreneur cannot be boss. What have they done, then? The most common approach in history – some of the entrepreneurs, manufacturers, and proprietors – not all, but some – seek some means of doing away with the consumer boss’s freedom to buy and sell.

If, for example, they can get the government to decree some special privilege for them, then they can be boss, and the consumers will have to buy their products instead of some other products the consumers really prefer. I’m going to illustrate the history of the protective tariff in the mythical country of Ruritania, where you have not been, and I haven’t either, but it’s in central Europe.

For years, the manufacturers of shoes in Ruritania had been lobbying for the Ruritanian government to impose a tariff tax on the importation of shoes. In 1920, the government finally imposed the tariff. A tariff tax was added on to the selling price of all imported shoes. The immediate effect: Imported shoes were priced out of the market. This ended the importation of foreign-made shoes into Ruritania.

The Ruritanian people now had to purchase the higher-priced, lower-quality domestic shoes or go without shoes. Of course, the people in Ruritania and the Ruritanian shoe industry loved the fact that they were now the boss. The Ruritanian people now had to buy their domestic-made shoes or go without shoes.

Since the custom of wearing shoes, especially in public, was long-established, the people were reluctant to give up shoes, as perhaps you might be. Well, the value of the government-imposed special privilege didn’t last for long. Other domestic manufacturers also wanted into the special privilege system. Thus, the domestic shoe industry rapidly expanded.

The result? The windfall gains enjoyed by the shoe industry in the early 1920s began to diminish as more and more manufacturers entered into the shoe business. Here’s another result of this imposed special privilege. Protectionism always causes a geographical shift in where products are produced.

The demand for foreign-made shoes has fallen, while the demand for domestic-made shoes has risen, as a direct result of the tariff. This brings to mind the question, so what? As long as I have to wear shoes, what difference does it make whether the shoes are made in geographical place A or geographical place B? It won’t make any difference to you at all unless you are looking for what kind of shoe?

The highest quality shoe at the lowest price. Who’s looking for this shoe? Every shoe buyer. You can’t find in the real world one buyer who’s looking for the lowest-quality shoe at the highest price. There is no such person.

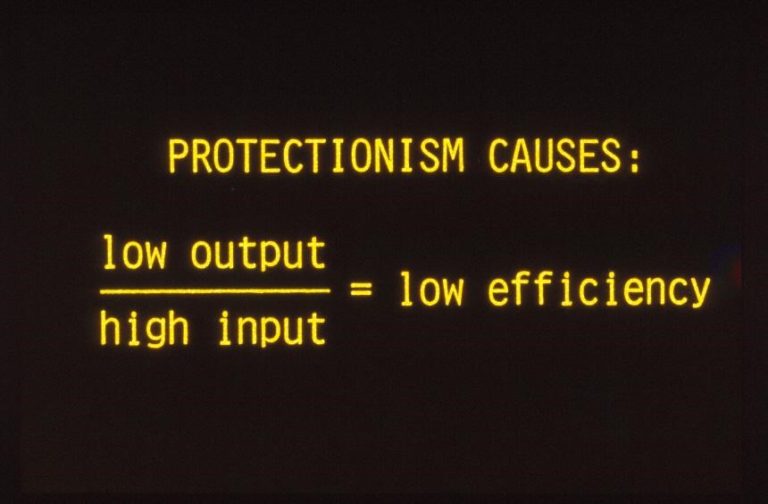

Let’s look at this simple equation that explains what protectionism always causes. Protectionism causes low output divided by high input equals low efficiency. High input means a lot of labor, tools, materials, and so forth going in with the resulting low output of products coming out the other end. Simple as that. High input, low output equals low efficiency every time.

In sharp contrast, let’s see what free trade causes, the exact opposite. This should be no surprise. Low input means a comparatively small amount of labor, tools, materials, and so forth going into the product here, and there’s a high output coming out. Your high output equals high efficiency.

But since there isn’t any free trade, Ruritania is experiencing a shoe industry that is growing both in size and, guess what? Inefficiency. The result: Some other domestic industries either shrink or are prevented from growing. This means, furthermore, the government’s interference with free trade is preventing one of the great prosperity solutions, namely the closest to zero but not zero solution for being allowed to flourish.

In Ruritania, do we want 100 percent of the people in the shoe industry? No. Do we want 0 percent of the people in the shoe industry? In general, no, unless outside of Ruritania they can produce shoes far better at much less cost, in which case it would even be advantageous to have zero people in the shoe industry in Ruritania. Do you see that? That even might be advantageous, if the outside shoes are so much cheaper and of such higher quality.

The Ruritanians are going in the wrong direction. They are going in the direction of 100 percent of the people in Ruritania, 100 percent of the capital in Ruritania being in the shoe industry. As they get closer and closer to 100 percent, in general, what happens? The more inefficient they will become in the shoe business.

Remember, the closest to zero but not zero solution only can be applied where there is what kind of a market? A free market. When the Ruritanians imposed a protective tariff on shoes, what did they do away with? The free market. In so doing, this will cause other losses for the Ruritanian people. Since the tariff has prevented altogether or at least sharply diminished the importation of shoes, every pair of shoes not imported represents some other Ruritanian product that cannot be what? Exported.

There is a simplex principle of exchange. If a nation does not import, it cannot export, and if it does not export it cannot import. Simple as that. The exporter always wants something in exchange for his goods, and the importer always wants something in exchange for his goods. When the principle of free trade is introduced, then the geographical location of buyers and sellers is irrelevant.

Where there is free trade, the entire concept of exporter and importer is irrelevant. You only have buyers and sellers. Doesn’t matter where things are made. It’s irrelevant. When any buyers and sellers arrive at a mutually agreeable price, where these buyers and sellers happen to live geographically is irrelevant.

As a result of the Ruritanian government’s tariff on shoes, the volume of Ruritania’s foreign trade is curtailed. In the end, not a single person in the world derives any advantage from the preservation of the old tariff, and so everyone is hurt by the drop in total output of mankind’s industrial production.

If the protectionist policy adopted by Ruritania were to be adopted by all nations for all products with rigid enforcement, international trade would be demolished. Every nation would be compelled to be economically self-sufficient. The result? All people would have to forgo the vast wealth, which the international division of labor gives them.

The repeal of the Ruritanian tariff on shoes, in the long run, must benefit whom? Everyone, Ruritanians and foreigners alike. However, it would remove the coercive advantage given by the government to those who have invested in the Ruritanian shoe industry. In other words, it would remove the short-run advantage of the Ruritanian workers who specialized in shoe production. A part of them would have to leave the shoe industry for some other work, change their occupation, or even emigrate from Ruritania.

We should not be surprised when the owners and their employees passionately fight against every attempt to either lower or abolish the tariff on shoes. Even though the effects of the tariff are injurious to everyone, their termination, in the short run, is, to be sure, a disadvantage to the special privileged groups.

But we must not lose sight of the fact that this special privilege is backed up with the violent enforcement of the government and their guns. These privileged groups who seek to preserve these tariffs are only small minorities. In Ruritania, only a small fraction of the total population is engaged in the shoe industry. They may experience loss of income from the abolition of the tariff on shoes, yes, but the immense majority of all buyers of shoes would all benefit from the sharp drop in shoe prices and the increase in quality.

Now, there are other arguments for the continuation of tariff confiscation. What if every domestic producer of products in a country is given a special tariff protection from better foreign products? What about that? It is said, if the government ends tariff confiscation and allows free trade, then every entrepreneur and every worker will suffer.

Let’s return to this point I made earlier. What is a justification offered by the government for every act of bureaucratic interventionism? Again, let’s look at it. It’s the same theme. You’ve already heard it here. “This act of violent government confiscation from the people will attain the greatest good for the greatest number.”

All governments defend their confiscatory policies. All governments tell the people they are confiscating the people’s choices in the interest of the people. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that the government claims, “Well, if we repeal this tariff confiscation, this will hurt every citizen in the nation.” You’re going to hear this.

Let me pose this question: When any government stops its violent confiscation of choice, can the act of ending violence harm anymore? The people are actually told, “If we stop directing violent action against you, this will hurt you.” Who believes this?

Almost everybody believes it, because it’s told to them by authority. When the government goes from tariff confiscation to freedom of choice and hence free trade, then the efficient industries will expand and prosper.

But what about the inefficient industries? Well, what about them? Dear friend, I don’t know how to tell you this, there is no law of nature that prevents any inefficient producer from learning how to become an efficient producer. Is there? I’ll tell you something: Everyone starts inefficient. Everyone is born inefficient. We all start there. You have to learn to be efficient, don’t you?

You don’t leave the womb being efficient. You leave the womb being inefficient. That’s true for all of us. One or two things happens before your final demise: Either you learned to be efficient or you didn’t. That covers all possibilities. One of the great incentives to learning to be efficient is you’re tired of being inefficient.

This will enhance their incentive to successfully compete and achieve even greater profits than they enjoyed while under the protection of government violence against foreign competition. If they are suddenly in a sink or swim alternative, this may spur them to new levels of entrepreneurial imagination and innovation.

But what if they suffer entrepreneurial loss? Could this happen? Sure. Who can experience entrepreneurial loss? Any entrepreneur at any time. Entrepreneurial loss, however, always means one thing: The consumer bosses are unwilling to pay a price for the product that exceeds the cost of production. That’s all it means.

When this happens, it is the operation of one of the greatest beneficial, progressive, positive domino effects of the free markets, and that is the closest to zero but not zero solution. It is only in a completely free market, as I’ve said, that this solution can effectively operate, and thus achieve, the greatest prosperity for the greatest number.

We need the closest to zero but not zero mechanism in full operation to optimize national prosperity. The consumer bosses, through their market votes, put the greatest number of tools of production into the hands of the most efficient super humanitarians. Even if in Ruritania the workers in the shoe industry experience, without the tariff, a decline in earnings, they also will experience a dramatic decline in the prices of products in general.

Every consumer product will greatly benefit. When the cost of products continues to fall, what happens to the standard of living? It goes up. What’s wrong with that? That’s how it goes up. The cost of products continues to fall, increases in quality, and continues to fall in price. That’s how the standard of living goes up. That’s how you do it. That’s what you want.

The people in the shoe industry will inherit, like everyone else, the many blessings of free trade, and so when free trade flourishes and every branch of industry is shifted to the location where the lowest comparative cost of production could be accomplished, this increase in the efficient productivity of labor also increases the total quantity of goods produced.

This is the lasting, continuous, long-run benefit from which free trade always secures to every member of the free society this bonanza. When you couple the application of international free trade with the principle of the free market system, the long-run trend is for the achievement of three universal benefits. This is what happens in a free society, the win-win society, all the same. A free market system – different ways of saying the same thing.

Here’s what you get, always. One, the quantity of products increases. Two, the quality of products increases. Three, the cost of products decreases. What’s wrong with that? That’s what we want. This ensures that the quality of life for everyone in society will continue to advance indefinitely.

One of the most popular national fallacies is that, somehow, tariff confiscation will bestow upon the nation’s wage earners a higher standard of living. Why is this a fallacy? What is the cause of a higher standard of living for the people? There must be a greater prosperity for the people.

Greater prosperity does not have a dozen sources. It only has one source. Can anyone, in his own words, tell me what I think that source is? What’s the road to prosperity? How do we get prosperity? More productive tools and fewer babies. The two go together. You’ve got to have both. It’s not just more tools. Prosperity is a principle that says essentially, in fewer words, you’ve got to produce tools of production at a faster rate than you produce babies. That’s where it comes from. The standard of living will only increase when you produce products faster than you produce people.

There is no act of government interventionism, which always involves violent confiscation, that will cause greater prosperity for the people. No act of government. That allows for how many exceptions? None. Even when the government, through interventionism, encourages a particular branch of production, there is always a regressive domino effect, and so the government does not have the power to encourage one branch of production except by curtailing other branches of production.

The government, through force, withdraws the factors of production away from those areas where the consumer bosses would have employed them and redirects them to those areas where the bureaucratic bosses want to impose them. As I explained earlier, the consumer boss is shoved aside by the bureaucratic boss.

The final argument advanced in favor of protectionism is the infant industries argument, which you’ve all heard. It is said that older, established industries have acquired a superior advantage as a result of their early start. You’ve heard this argument for tariffs? This advantage, it is said, prevents the development of new, competing plants or factories from even getting started.

The advocate of protection for the infant industry will admit that, well, the cost of this protection, perhaps, is temporarily high, but the sacrifices made now will be repaid by the gains to be reaped later. Well, the truth of the matter is, when profit is the goal, the establishment of any infant industry is advantageous only if the superiority of the new location is momentous, that is, large.

Here’s a simple test. When you can purchase the product from the old factory for less cost than you can purchase it for from the new factory, then, as the popular expression goes, forget it. Forget the new factory. You don’t need one. The solution to the infant industry’s problem is simple. Unless the potential for profit at the new location is momentous, then the infant industry should not be built in the first place. That’s the solution. It couldn’t be simpler.

But if the potential for economic success is there, then the new plants will compete successfully with the older, established plants without the necessity of any government protection from the efficiency of the old plant. If the potential for profit is absent, then the protection granted them is wasteful. This is true even when the protection is only temporary.

There is no way, in fact, to be certain the protection is only temporary until it’s abolished, anyhow. In every case, the tariff is a subsidy for some special privileged group. Think of tariff always as a form of special privilege imposed upon society through violent means.

In the last analysis, it is the consumer who always gets stuck with the tariff bill. It is the forgotten consumer who pays for every tariff because the consumer pays for every tax. The actual use of the term tariff by politicians to describe new tariff legislation has perhaps fallen out of favor, but since the concept of government control has not fallen out of favor, the bureaucrats are always coming up with new names for old controls. They’re good at thinking these up all the time, new names for ways to get you.

They came up with things like quotas on imports and exports. If you either export or import, the government assigns you a quota on the quantity of goods that you’re allowed to export or import. Some of the new bureaucratic terms for control even have a nice-sounding name. The best thing you can ever do if you’re a part of the bureaucratic establishment is think up nice-sounding names of ways to control people without their permission and confiscate their choices.

Good-sounding ones like, most-favored nation agreements or bilateral agreements or multilateral agreements. All of these new names can be translated into one concept, i.e. government confiscation of choice. In the case of these international agreements, the politicians and the bureaucrats from the various nations agree among themselves what restrictions upon free trade will be imposed upon their own people and what restrictions will be imposed upon the people of other nations.

That’s what they mean by one of these agreements. An international agreement? What does that mean? It always means an agreement between politicians and bureaucrats, not an agreement between the people of one nation and the people of another nation. In other words, there is an international agreement on what choices politicians and bureaucrats will confiscate from the people. That’s what an international agreement means.

They explained this to you in school, right?

No, they didn’t. We’ll come to school later. I hope you’re here for that session. Other popular terms for still more bureaucratic controls are – here’s a nice-sounding one – fair trade laws. Everybody’s for fairness, right? Fair trade laws. Exchange controls. Bulk buying and selling, and so forth.

Then there are all kinds of politically financed subsidies designed to subsidize foreign bureaucracies. There are all kinds of international giveaway programs. What does that mean, giveaway? Giveaways that always involve what? The generosity of politicians and bureaucrats giving away property that they first had to confiscate from whom? Their own people, then doling it out to people abroad.

Let’s see if we can reach a simplex generalization that identifies the effect upon the people of all of these government controls. Every government control involves one action, the confiscation of choice. These government confiscations of choice always set in motion various regressive domino effects. For example, the protective tariff always diverts production from those geographical locations where production is efficient to those geographical locations where production is inefficient.

A tariff converts efficient production into inefficient production. A tariff never increases total production. Instead, it always decreases total production. All tariffs restrict both the production of wealth and the access to wealth.

Since all tariffs decelerate the accumulation of the tools of production, they are always called, in this seminar, regressive. Each act of bureaucratic interventionism will affect various individuals and groups in a different way. For some, the interventionism will be a great gain. For others, it will be a great loss.

Interventionism may temporarily improve some people’s economic level, but the same interventionism will impose a disadvantage and loss upon the vast majority of people. It is increasingly popular for individuals to demand government restrictions upon entrepreneurs and their business ventures. But if you look more closely, you are likely to find an individual demanding special privilege for whom? Himself.

Whenever any individual is favored by government interventionism, he has acquired special privilege at the expense of his fellow humans. The law of human action tells us we take actions to gain greater satisfaction. The prime measure of a man’s and woman’s character is how they seek greater satisfaction.

There are two means to greater satisfaction.

One, strive for greater satisfaction through the loss of another. Two, strive for greater satisfaction through the gain of another. That’s your choice. From the time you are born it’s your choice. What will you do? That’s it for everybody. What will they do?

To take a great step forward toward the enhancement of your own greater satisfaction, here’s some advice that will reward you the rest of your life, if you never hear another thing I say. You ought to know this implicitly, but if not, I’m giving it to you explicitly. And that is, seek out those people, surround yourself with those people, who strive toward greater satisfaction through the gain of others.

Imagine what a satisfactory life you can lead by surrounding yourself with those who actively seek gain through the gain of others. And you only associate with these people. These are your friends. You can’t pick your relatives, but you may have to give up relatives who seek gain through the loss of everyone else. That’s a relative not worth knowing and certainly not worth being related to.

But don’t make the mistake of marrying into that. Don’t marry into a clan of people who are seeking gain through the loss of others. That’s a huge blunder to step into. To understand why some humans aim at greater satisfaction through the loss of others while others go after satisfaction through the gain of others requires a science and a theory of human action which I will give you here in four days.

I’m giving you the foundation to answer this question. Well, why is it that some go after gain through the gain of others and others go after gain through the loss of others? Why does this happen? I’ll give you a clue as to how it happens. This may be hard to believe, but I’ll justify it. It only happens where you have people who are taking actions who don’t have the foggiest idea of what they’re doing.

There’s all kinds of street expressions for this, which we’ve heard before. I’m tempted to share with you one that the drill sergeant when I was in the Army used to use all the time, but I won’t.

Say, for example, that a man doesn’t know what he’s doing. That’s a euphemism for all kinds of things.

Whenever the bureaucracy imposes a tariff tax, the tax was caused by someone aiming to gain greater satisfaction through the loss of another. The tariff tax always lowers the standard of living of the consumer. The consumer is forced to pay a higher price for the tariff-taxed product. The importer of the product, if he can still sell it, passes the tax on to the consumer.

The consumer is stuck with one more tax burden, or the consumer must pay a higher price for a domestic shoe. But that’s all right, say the domestic shoe producers who lobbied to get a tariff tax on the imported Italian shoes in the first place. We love the tariff, they say. It’s more money in our pockets, say the domestic shoe manufacturers.

A producer who demands protective tariffs is always demanding what? Special privilege for whom? Himself. He seeks protection from what? He says, I must, at all costs, be protected from what? Those people who are doing a better job of serving the consumer bosses. “I must have protection from these people.” Well, what does this mean? He does not possess the courage to compete in the marketplace for the favor of the consumer boss.

That takes courage, because all consumer bosses are fickle, capricious. No loyalty. As soon as a better mousetrap is built, “I want that one. It’s cheaper and better. I want that one.” They’re fickle. There’s a huge risk that goes with trying to please the consumer bosses – big risk. It’s so big, hardly anybody wants to do it.

What happens is, instead of seeking the favor of the consumer bosses, you seek special favor from the bureaucratic bosses – that is, those people who want protective tariffs. Whenever the government grants special privilege to any one business, it must impose its violence against some other business.

When the government grants special privilege to small businesses, it also imposes a handicap upon big businesses. But the small businessmen, in general, rejoice. When the government, through violent force, places a restrictive handicap upon the operation of chain stores, the small shopkeepers all rejoice.

In so doing, the government takes on the function of imposing a handicap upon certain targets of its violence. My Webster’s Dictionary says, “handicap: a competition in which difficulties are imposed on the superior contestants. An advantage given to the inferior to make their chance of winning equal. Something that hampers a person or hinders him or gives him a disadvantage.”

The handicap is imposed upon those producers who exhibit too much imagination, competence, and skill at serving the demands of the consumer bosses. The government assumes the role of supreme handicapper by literally imposing handicaps upon those super humanitarians who best serve the consumer bosses.

In contrast, those who fail to serve the consumers are given a special privilege from the government. But the special privilege is only an advantage for a limited time. In the long run, the privileged branch of production always attracts newcomers who also want in on the benefits. They want in on the special privilege. “This is a good deal.”

This new competition for special privilege then diminishes or eliminates the potential for gain. Everybody wants in on it. This is why those who acquire special privilege are never satisfied. They always demand more and more. Have you noticed? The people who get freebies, especially when it’s tax-supported, always want more. They always demand more. It’s never enough. Have you noticed that?

The more privilege they attain, the more they demand, because the old privileges lose their advantage. Once a particular class of producers is granted special privilege, they always behave as if they have a right to the privilege.

If the privileged class is domestic shoe manufacturers, they will scream loudly for the maintenance of the tariff protection from the foreign super humanitarians who are producing better shoes for less money. In sharp contrast, what will the buyers have to say on the subject of the tariff on imported shoes? What will they have to say?

Probably nothing at all. Why? They won’t see the regressive domino effect of the tariff. They will not see that the tariff tax on imported shoes is forcing the entire public to subsidize the small minority of domestic shoe manufacturers.

To illustrate, let’s assume in America you have 200 million pairs of shoes purchased. On average, let’s say one pair of shoes a year. If due to the tariff tax each consumer must pay, for example, $5 more per pair for either foreign or domestic shoes as a result of the tariff, then what does that mean?

Two hundred million shoe buyers times $5 extra per pair is what? One billion dollars, isn’t it? What does that mean? The people have had $1 billion confiscated from them and are that much poorer, and they don’t even know it. Hardly any of the $200 million shoe buyers are aware they have been forced to subsidize the domestic shoe producer and are $1 billion poorer. Do you see that hardly any of them know this?

But if there were not a tariff, they could still purchase the same quality imported shoe and also have $1 billion to spend on other products, raising their standard of living by how much? A billion dollars. That’s not insignificant, is it? Let’s look at the growing concern for America’s inability to compete with foreign manufacturers in many areas of production.

The major cause has been the growth of regressive human actions aimed at entrepreneurs. I said regressive action in some way slows down the accumulation of the tools of production. Slow down the accumulation of tools, and you slow down what?

Prosperity, yes. One of the most popular forms of bureaucratic interventionism in this century has been the corporate income tax. Its popularity is due to the fact that most of the American people do not have ownership in what? A corporation. Therefore, the majority of people who do not have ownership in a corporation are generally in support of the government forcing the minority of corporation owners to pay corporation taxes. In other words, here’s what happens: The majority of people favor the idea of forcing the minority of people to pay a subsidy to the majority of people. The majority of people think, “That’s great. We love it.” But due to the regressive domino effect of this government confiscation from the corporation, there are two classes of losers.

One is the minority who have corporate ownership, and, two, the majority who do not, which includes a class how large?

That’s everybody. When the government uses the corporation tax to confiscate corporation profits, it is much more than the profit that is confiscated. Every dollar of profit that is confiscated cannot be reinvested in, one, replacement of worn-out tools, and two, replacement of obsolete tools, and three, purchase of new tools, and four, development of new tools.

It is common and has been for half of a corporation’s profit to be confiscated through corporate income taxes. But when the government confiscates profits, the regressive domino effect is, they confiscate the tools of production, which in turn confiscate what would have been greater prosperity for the people.

When the government confiscates from a corporation the tools of production, there is another regressive domino effect. It cannot compete as successfully with whom? Foreign corporations. Those corporations that make the greatest investment in the tools of production always have the advantage, even if the competition comes from cheap, foreign labor.

One of the main reasons, for example, not the only reason, but a significant reason for Japanese prosperity relative to American prosperity is, the Japanese, for decades, have been putting more money in investing in, guess what, the tools of Japanese production, than Americans have been putting in investment into the tools of American production.

The results speak for themselves. It’s not the only difference, but that’s one of them. No matter how cheap the labor, no matter how great the multitude of laborers, they cannot successfully compete with two things: one, more machines, and, two, better machines. And they certainly cannot compete with both. This has been demonstrated since the dawn of the machine age.

The most significant example of the blessings of free trade can be found within the borders of the continental United States. For the first 100 years of the American republic, from 1787 to 1887, there were virtually no trade restrictions between any of the states or territories, for 100 years. That was a huge boom.

Even with the internal meddling that we’ve had with interstate commerce and the advent of the Interstate Commerce Commission in 1887, nevertheless, for 200 years, we’ve been blessed with largely unhampered free trades between the states and territories in the Union. Within the borders of the United States has been the largest landmass in the world where something has been allowed to flourish. Guess what? Free trade has flourished in the United States.

That’s the largest area where free trade has ever been allowed to flourish. That’s been the experience for more than two centuries. Largely because we allowed free trade among the states, this nation became the wealthiest nation in the world. That was one of the prime reasons. They didn’t make that mistake when they started out.

But what if we had allowed the protectionists to prevail? There are protectionists all over the place, because there are all kinds of people who want what? They want to gain something through your loss, and if they can get the government to help them, that’s the best way to do it. If you don’t go along with it, you will be fined, imprisoned, or killed.

The best thing you can do is to get most of the educated people to go along with this, and then you’ve got it made. That’s all you’ve got to do. In other words, all you’ve got to do is indoctrinate the people who go to school, and the longer they go to school, the greater the indoctrination.

If we had allowed protectionism between the states of the union, American prosperity would have been squelched. It would have been strangled. We didn’t, with some exceptions, make that mistake on a large-scale basis. Imagine, though, where we would be today if every state had its own trade barriers, protection tariffs, border guards, customs officials?

Think about it. Do you think there would be any internal harmony in this nation? You know what you would have? You would have 50 states engaged in varying degrees of war with one another. That is exactly the situation we have in the world today between various scores of nations where they do have trade barriers fully intact.

It was Frederic Bastiat, whom I quoted earlier, an obscure Frenchman who died in 1848, to whom I give a lot of credit to intellectually for what Bastiat taught me, and one of his great lines was, “If goods do not cross frontiers, armies will.” That was true then, and it’s true now, because it is a truism. It’s a principle.

To complete this session that has dealt with that aspect of government interventionism named the protective tariff, I proposed this question to you earlier. Can any producer of surplus wealth anywhere in the world sell some of his surplus wealth to any willing buyer anywhere in the world without causing harm to any third party anywhere in the world?

At the end of the lecture, I hope the question answers itself. When both A and B, regardless of where they live, have the freedom to trade, and both A and B agree on the terms of the trade, there is not one third party called C who can be harmed, assuming, of course, that A and B are not in violation of a prior contract with C; assuming no prior contract.

As I will clearly demonstrate later, not only is C not harmed, but C’s potential wealth has been increased by both A and B’s freedom to trade and by the actual trade itself. How important is the freedom to exchange? We’ll answer the question with one sentence: Free exchange is the foundation of wealth. A society can only prosper as the magnitude of the total number of market exchanges continues to increase.

Free the People publishes opinion-based articles from contributing writers. The opinions and ideas expressed do not always reflect the opinions and ideas that Free the People endorses. We believe in free speech, and in providing a platform for open dialogue. Feel free to leave a comment.