As “Armageddon-out-a here” continues at a breakneck pace—at the hands of an ever increasing behemoth of bureaucracy and its new, armed, deadly force using 87,000 new IRS agents—I thought it might be a nice reprieve from the usual siren song of horror to focus on something a little more uplifting and bright from history.

I grew up in a small town in Wyoming and I go back often to reminisce and be engrossed in a bygone era. The town has changed very little in the 35 years since we left for brighter economic horizons in Colorado. To be sure, there are a few more people and the restaurants are a little more prolific than they were in 1985, but all in all the town of Sheridan, Wyoming changes very little. The parade for the Rodeo is the same every summer, the people are the same, and the spirit of this small western town is as robust and beautiful as it has ever been. The needle pointing towards the wild-wokeness of the urban world seems very much to be broken in this sleepy, beautiful place. My recent trip back there this July was filled with the same activities I’ve grown accustomed to and it was as wonderful as always. No matter the number of years that pass, the place seems to channel its inner David Byrne and remain the “same as it ever was.”

One frequent stop on my travels in this amazing slice of the West is the Brinton Museum in Bighorn. Bighorn is a small town of 400 people just south of Sheridan and is home to, in one of the more odd combinations of things, the finest fly fishing, horse polo, and western art anywhere in the United States. When I was younger, my parents would drag any out-of-town company to this museum at the foot of the mountains and I would spend time in drudgery as an 8-year-old looking at an old house filled with western art.

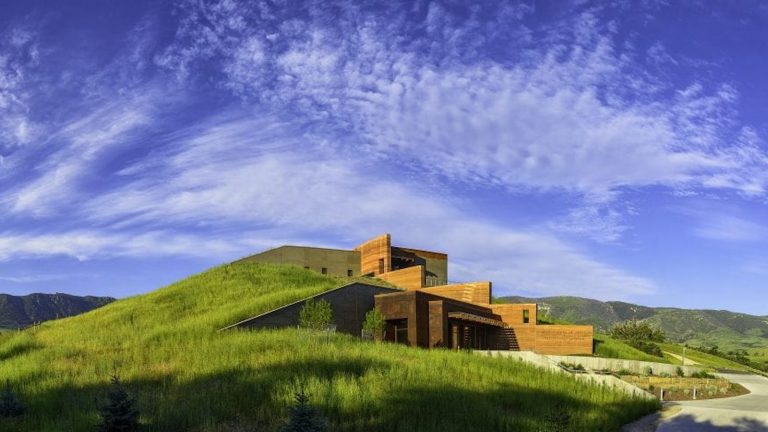

As is often the case with age, things that were uninteresting to the mind of my youth, are now captivating and a “must see” for myself and any friends I can coerce to come to the mountains with us when we travel there in the summer as a family. The museum today is a beautiful modernist building that the Forrest Mars foundation donated to the community, and the local bank sponsors free admission to one of the best collections of Native American archives, along with paintings and sculptures by Frederic Remington, Charles Russell, and others.

I get it… this is a website usually filled with politics and this article doesn’t have much to do with the current dose of insanity pumping from the bowels of DC. If you’re saying, “who cares about your 8-year-old self,” try to stick with this. There’s a point to be made about capitalism, art, and the way the wealthy saw their responsibility to culture that will satisfy even the most stingy libertarian political wonks.

Bradford Brinton, the museum’s namesake, was a wealthy capitalist from Illinois. The businesses his grandfather started—Peru Plow and Wheel Company and the Grand Detour Plow Company—are a part of the family tree of the J.I. Case tractor company. His family’s company was purchased by the Case company, and Brinton became the manager and director of the company. His skills as a businessman helped build it into one of the best tractor brands in farming. Because of that success, he was able to take his earnings and purchase real estate in the Bighorns and other locations. His ability to grow a business allowed him to become exceedingly wealthy, and his skills as a manager are arguably some of the reason that the Case company has the longevity it has.

The ranch he purchased in Bighorn sits upon a stunning setting and the grounds and home are beautifully preserved. The home itself is filled with a collection of western art rarely seen anywhere. Brinton was acquainted with some of the West’s most famous artists. He wanted his home and ancillary buildings to be filled with the artwork of the region. He hoped that his guests at the ranch in Bighorn would be captured by the spirit of the West, and that by being surrounded by the imagery and tactile pieces of this frontier, they would feel the rugged spirit and beauty that he did.

Over the years and with a significant personal investment, Brinton built up a massive collection of artwork. He would commission fledgling artists to create art for his purchase. He would ask them to paint a frisée along the top of the dining room or create a new piece for his fishing cabin. He would purchase their sculptures and paintings to hang in the home to help set the tone and aesthetic for this beautiful property. Brinton recognized the talents of these artists and understood that his capital investment in these painters and sculptors were helping them continue to pursue their talents and also have enough money to eat. It wasn’t charity or flippant spending of money for the sake of it, but instead a true exchange of services that allowed both parties to ultimately benefit and continue on in their pursuits.

Artists have always struggled to make money during their lifetimes. The list of famous painters and sculptors who died penniless is a long one. Most of the time, culture struggles to recognize the genius of someone during their lives. With rare exception, the commercial endeavor of artistry does not translate into a life of luxury. Because of this perceived disadvantaged lifestyle, many of America’s artists today scream for public funding for their endeavors. Governments for their part, glom onto this story of sadness and advocate for public funding for these beleaguered souls. Part of the sales pitch for the Affordable Health Care act was that people would no longer have to pay for health care, and thus they could quit their job and spend their free time developing their craft and making art for our society. The thought is that without public funding and taxpayer extortion, art could never be created as prolifically or beautifully. They argue that artists need to be freed from the burdens of financial responsibility so they can be released to create the art we all value as a society.

A quick and anecdotal analysis of this statement however demonstrates, as is usually the case with hyperbole, that the statement is completely detached from reality. The starving musicians first album is nearly always better than their second. The artist who makes no money from their paintings has a deeper honesty in their work than someone who lives a life of affluence and paints for fun or because they are insatiably driven. Art is best with hardship as its underlying canvas. When people are given a disproportionate amount of money to create things, they generally generate bland, uninspiring “art” that falls flat and has no shelf life.

When I was a young aspiring musician myself, I traveled around the country in my minivan doing what I could to get enough money from the night’s show to gas up the car and get to the next city. Sometimes I would sell enough CDs to enjoy an excursion to something the town I was in had to offer. One such afternoon in Abilene, Texas, I went to one of their art museums. On display was an exhibit from the former Soviet Union. Most of the work was technically excellent—but the subject matter was entirely about the support of the State. The artwork was a disappointment to my eye. It was flat, bland, and boring. While the individual artist’s skills were on display, the subject being painted was uninteresting. Propaganda very rarely holds up as real art. There are few, for instance, that would argue that artwork from the Spanish Revolution sponsored by the state can outshine Guernica by Picasso. The subject matter was the same… but the outcome is profoundly different. The same was true of this exhibit of state sponsored artwork in Abilene. There is something inherent in the soul of humanity that raises its guard up when something is forced. Art by definition is provoking, inspiring, beautiful, and makes the mind wonder what the artist is trying to convey. The state sponsored versions of this are like bubblegum—brightly colored, technically achieved, but have no longevity in their pull on the human mind or heart.

The last time I was at the Brinton museum this summer, I realized that there was a fascinating intersection of capitalism, talent, and commerce that had happened at this ranch, and in the lives of those that interacted with it. Bradford Brinton was willing to spend his money on the talents of the artists that were in his sphere. He recognized their capabilities and also saw that he could benefit by paying them to create the art that would beautify his world. It made me realize that in that simpler world free of tax status, W-9s, and other money making inhibitors, Brinton was able to help and provide benefit for the artists so that their careers could eventually flourish. He likely saw it as a part of his responsibility as a wealthy capitalist to pay for the talents he was requesting the use of. In the end, everyone in the story benefited. Brinton was able to amass a collection of art that is now viewed as priceless. Remington and Russel were able to pursue their careers and become the most famous western artists of their era. All along, both parties were still pursuing their goals and mutually benefiting from the exchange.

This is the beauty of the invisible hand. Brinton was exchanging a portion of his rewarded talents for the talents of others. Remington and Russel didn’t have to be great businessmen. Instead, they could focus on the art in front of them and still purchase the supplies and goods to live on because of this economic exchange. The story of these people demonstrate to me something incredibly profound. Each human is created uniquely and their talents are disproportionate in the areas of their interests or focus. Brinton was a great businessman with a vision for the West and his property, but he also needed the artist to help him achieve that vision. They all used the heights of their talents to individually benefit—and capitalism was the mechanism that made it all possible. There was no transfer of wealth from one person to another with an intervening IRS agent in between. No one was held at gunpoint to make this exchange happen; it was voluntary, beneficial, and simple.

Capitalism is a beautiful art, and art is beautiful because of capitalism.

Add comment