What’s the Matter with Courts Today? What Private Justice Looks Like

My colleague Daniel Horowitz is fond of pointing out that the current system of government courts routinely exceeds its authority, makes questionable judgments, and acts as a de facto lawmaker in spite of the limited role prescribed by the Constitution for the judicial branch. In addition to those legitimate criticisms of the courts, there’s a fundamental, if rather prosaic, problem: They simply don’t work.

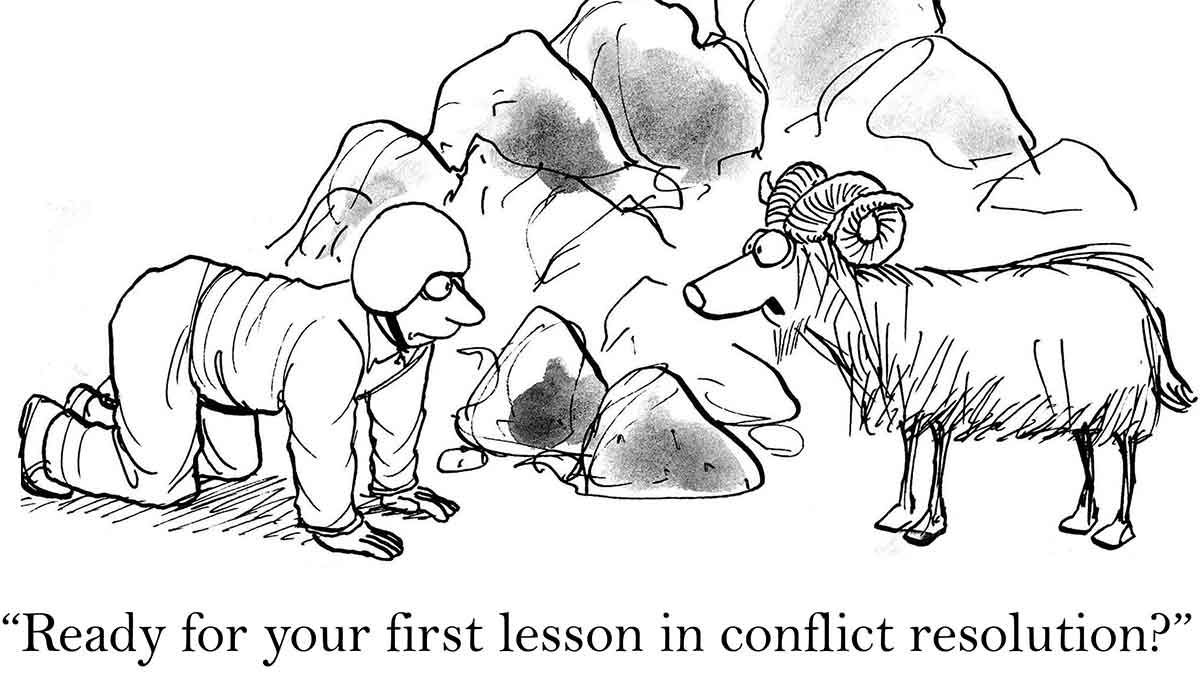

Imagine you and someone with whom you do business have a dispute. Maybe a roofer failed to do his job, and now rain is pouring into your house. Maybe you’ve been cheated by an unscrupulous restaurateur whose food fails to live up to the advertised standard. It could be any number of things, for we live in a world of constant commerce. What do you think your chances are of obtaining satisfaction if you take the offending party to court?

In most cases, pursuing a solution through the legal system is hardly worth the effort. The monetary cost of attorneys, extended delays, the appeal process, negotiations, and settlements are all impediments to justice. For most of us, even the cost of small claims court is prohibitive. And if we manage to scrape together the money to file a claim, the process is so torturously slow that it could be years before we see any reward for our efforts.

And yet, in the midst of so obviously a broken system, there remain a great many learned persons who insist that government, and only government, can resolve differences arising among the population, when in point of fact, the private sector quickly and efficiently handles these sorts of cases all the time, with so little hassle that people barely notice.

At the recent International Students for Liberty Conference, economics professor Edward Stringham offered a few illustrations of how private dispute resolution has been — and continues to be — handled all over the world. These methods range, from the marvelously sophisticated to the crude and makeshift, but they all do a reasonably good job of keeping people honest, or at least a better job than the all-powerful government has heretofore managed.

Perhaps the simplest form of contract enforcement that many of us use every day is the only review system of sites like Yelp and Angie’s List. While not particularly effective at granting restitution to customers who have been treated badly, these reviews, visible to every potential customer, provide a strong incentive for companies to fulfill their contracts and allow wronged parties to express their grievances in a painfully public way.

Woe betide the business that starts to rack up one-star reviews. It will not likely be around for long. Thus, not only is good behavior enforced through direct financial repercussions, but when something does go wrong there is every reason for the business owner to want to make it right through high quality customer service, all in the interest of avoiding bad reviews that could destroy his reputation. Online reviews effectively impose the discipline of a small, close-knit community on a large and impersonal market.

But customer reviews are only the crudest form of private contract enforcement. For occasions when the stakes are higher, and the costs of fraud much greater, something else is required. For major construction projects, that something comes in the form of bonding companies. A bonding company essentially sells insurance, guaranteeing that a particular service is carried out in a competent and timely fashion. Contractors are bonded after a rigorous examination of their capabilities, and they can take that bond to their customers as proof that they can do what is required.

Mr. Stringham used the example of a company that installs kitchens in skyscrapers. Building a skyscraper is a very costly and time-consuming endeavor, and delays or incompetence can make those costs rise even further, so it is important that no one be allowed to shirk. If a bonded contractor fails to fulfill its contract, the bonding company compensates the customer for his loss.

Of course, it’s in everyone’s interest that this not happen. The contractor doesn’t want to lose his bond (a fate, which would essentially make him unhirable), the bonding company doesn’t want to have to pay out large sums of money, and the customer wants his skyscraper finished on time. It is this alignment of incentives that makes the system work so well, an incentive structure, I might add, that is lacking in government courts.

There are historical examples as well. When stock markets first emerged in Amsterdam and London, government courts, viewing stock trading as a form of gambling, refused to enforce contracts. The traders involved quickly developed self-enforcement mechanisms and learned to resolve disputes internally, resulting in remarkably well-functioning markets.

Apologists for big government want us to believe that those things that government does wouldn’t otherwise be possible. However, it only takes a cursory glance around our society to see that not only is it possible to resolve disputes without courts, but it also happens all the time.

This article originally appeared on Conservative Review.

Free the People publishes opinion-based articles from contributing writers. The opinions and ideas expressed do not always reflect the opinions and ideas that Free the People endorses. We believe in free speech, and in providing a platform for open dialogue. Feel free to leave a comment.