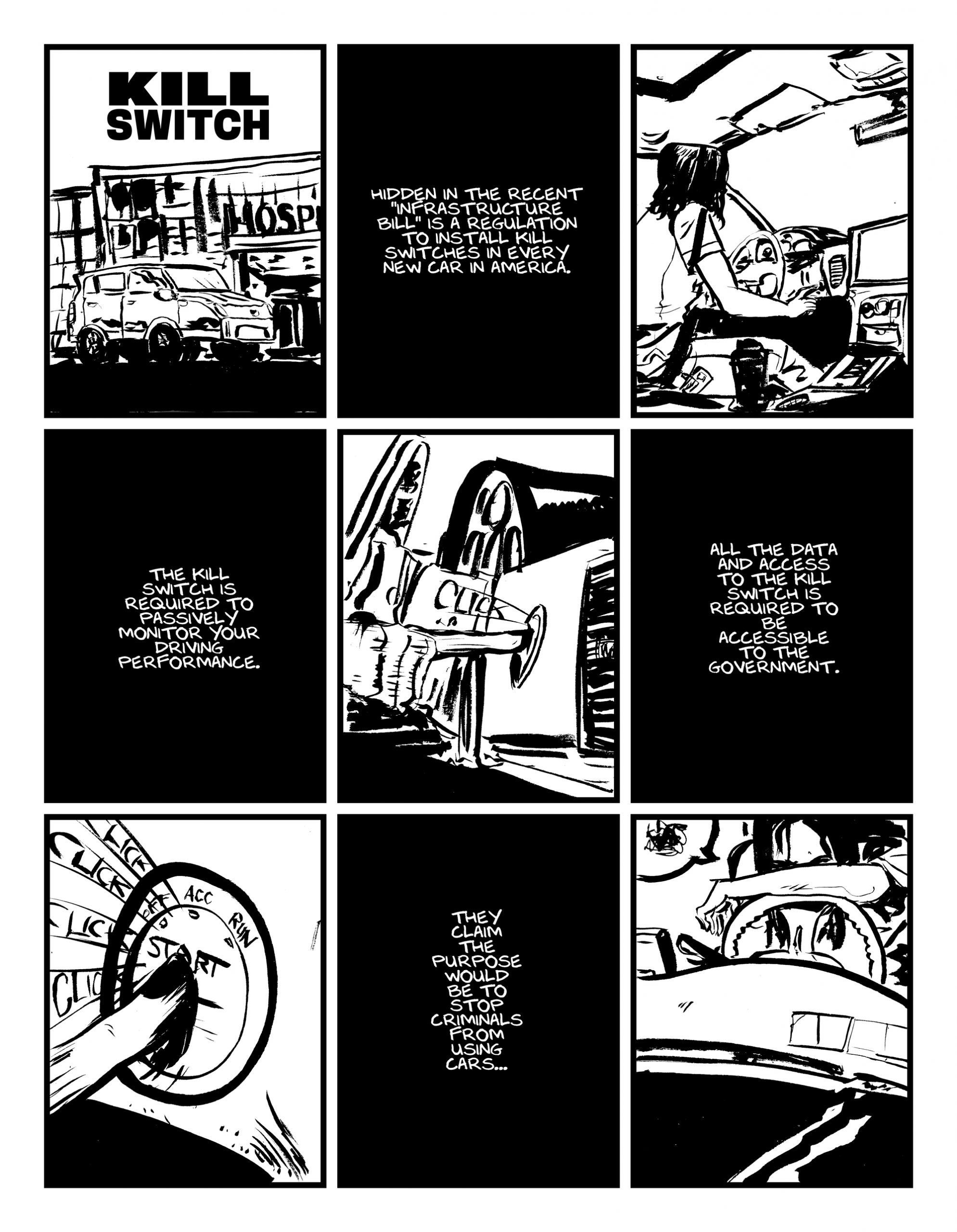

Automobile Kill Switches: The Latest Salvo in the War Against Autonomy

For years, there has been a push make cars “smarter,” with more electronics, onboard computer systems, and features designed to protect drivers from hazardous conditions, other motorists, and most of all, themselves. Whereas a few decades ago anyone with a wrench and a can-do attitude could crack open a vehicle and make repairs or modifications, the simple act of self-maintenance has become all but impossible for anyone without an advanced computer science degree. Cars beep at you when you forget to put on your seatbelt, tell you when you’re drifting out of your lane, and will even slow down if you get too close to another vehicle. The move towards self-driving cars offers to remove the human element from driving entirely, to the delight of some and the dismay of others.

As someone who hasn’t got behind the wheel of a car for more than twenty years, I personally find the basic idea of self-driving cars exciting and full of potential. They could increase mobility for people unable or unwilling to drive, and could increase efficiency and save lives for things like cross-country trucking, a job which is famously hard on those forced to perform it. But as with everything good in life, the government just has to come along and ruin it with its evil machinations, turning the potential to enhance human freedom into something designed to constrain it.

Buried deep in the bowels of the infrastructure bill signed by Joe Biden last year was a provision few took notice of, a requirement that every new vehicle sold in the United States be equipped with new technology designed to prevent drunk driving by 2026.

Nobody approves of drunk driving, so it’s not surprising that this was able to sneak through without much attention, but a deeper look into what the law actually allows reveals something far more sinister than merely keeping whinos from drunkenly mowing down pedestrians.

Typically abdicating most of its lawmaking duties, Congress has left most of the details of what this technology will actually look like to a regulatory agency, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, but the basic requirements are that cars be able to passively monitor drivers’ behavior or blood alcohol levels, and to stop cars from functioning when driven by an impaired person. This last provision is being described by critics as a “kill switch,” largely because that’s what it is.

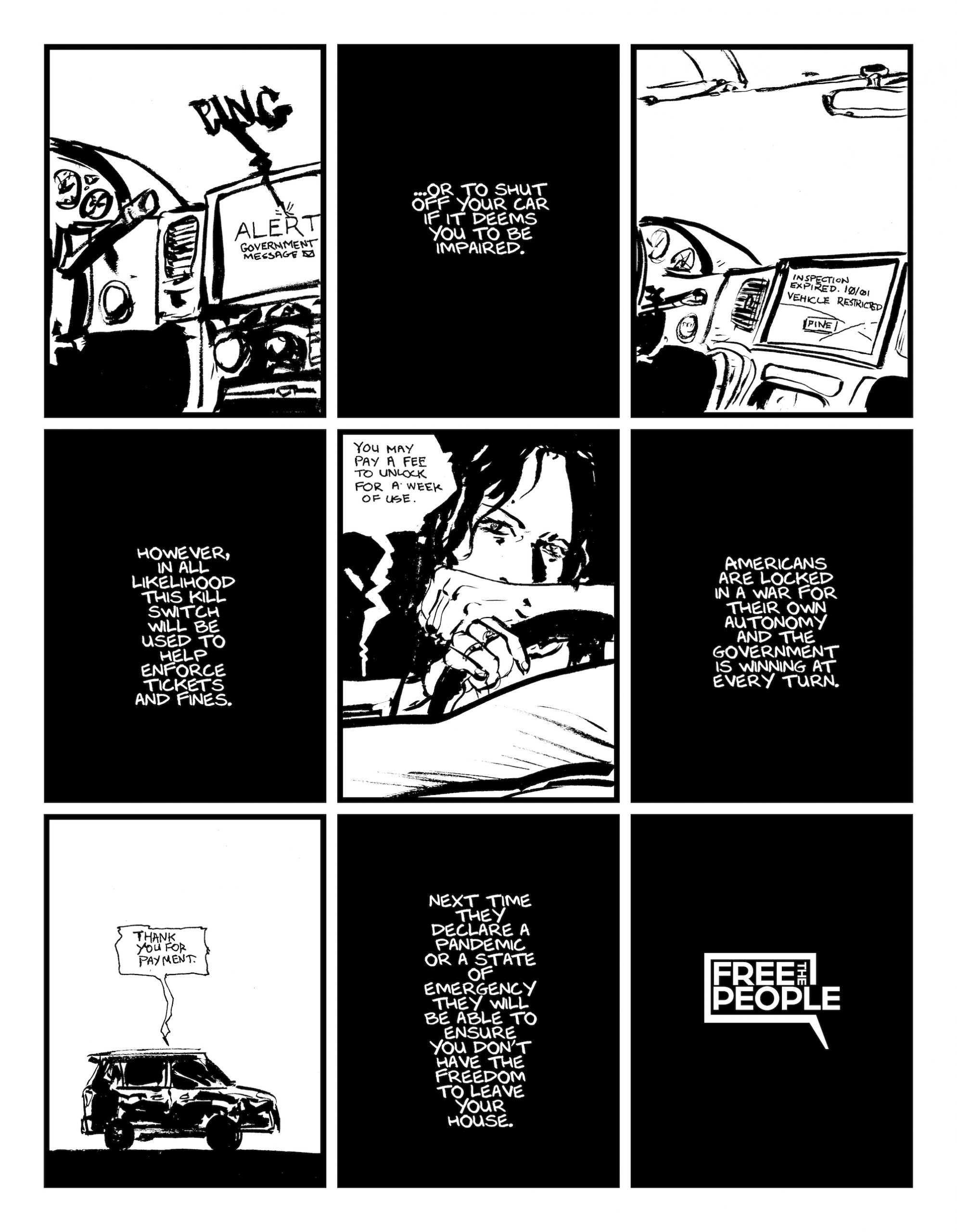

The Associated Press was quick to run defense for the administration, publishing a “fact check” article claiming that any anxiety over this sudden and invasive surveillance is unwarranted. Like most of these partisan fact checks, this one largely confirms what it is attempting to deny. One of the people working on this project, in an apparent effort to reassure drivers, said that his team is “considering systems that could warn an impaired driver, prevent an impaired driver from moving the vehicle, or reduce the speed of the vehicle and get it safely home. He said the term ‘kill switch’ is hyperbole, since none of the options being considered would include the risky move of lurching a fast-moving vehicle to an abrupt stop.” This is the textbook definition of the straw man fallacy, in which an opposition position is misrepresented in order to make it easy to argue against. No one is worried about kill switches because of safety concerns with bringing moving cars to a sudden stop. We are worried about the government’s ability to control our movements and reduce our autonomy. And since the technology in question doesn’t even exist yet (the NHTSA has several years to finish developing it) you can’t simply claim that any concern about it what it might be capable of is “false.”

The basic fear is simply this: if a regulatory board can decide under what conditions cars can continue to function, what reason is there to believe that this capability won’t be expanded in the future?

If today ‘s automobiles can stop drunk people from driving, it would be naïve to imagine that tomorrow’s cars won’t be able to stop people for other reasons. What kind of reasons? Well, maybe people with an arrest warrant will be stopped. That doesn’t sound too bad, right? What about the next time there’s a pandemic and the government decides we shouldn’t be allowed to leave our homes? Does anyone imagine that no one is planning to use this or similar technology in such a way in the future?

You can call this a slippery slope fallacy if you like, but I call it being a perceptive observer of history. Governments take every chance they can get to exert more control over their citizens; they always have. In China, the social credit system (which some in America have praised as a model we should adopt) allows the government to deny citizens access to certain parts of society if they do not behave in certain ways. How delighted Chinese politicians would be to be able to curb unrest by simply deactivating the vehicles of troublemakers. After all, it’s hard to have an organized protest if no one is able to drive to it. Even better, it’s hard to show up to vote in the next election if your government-controlled car won’t let you.

Again, the AP insists that the data collected by these alcohol-monitoring systems will never leave the vehicle and will never be accessible by members of law enforcement. And again, I remind the reader that the technology hasn’t been finalized yet, so any claims about what it can and cannot do are as speculative as anything I’ve laid out here. We were also told that our data was secure with the NSA, until it turned out that government agents were spying on just about every aspect of our lives. Anyone asking you to blindly trust that the government will not abuse its new toys for nefarious purposes is asking you to be willfully ignorant of history, political science, and human nature itself.

The ability to move freely is one of the most essential freedoms we have. Anyone who can control our ability to travel at will, controls just about every aspect of our lives. It’s why automated cars feature in so many science fiction dystopias, such as in the films Minority Report and Equilibrium and Total Recall (both based on stories by Philip K. Dick), in which the heroes have to overcome automatic vehicles capable of preventing them from going where they want to go. The Rush song Red Barchetta, inspired by a science fiction story, imagines a world in which human-controlled cars are illegal, and driving is undertaken as an act of rebellion. I remain somewhat excited by the prospect of self-driving cars, but not if it means taking away our freedom to drive ourselves. This infrastructure bill is just the latest step in a long slide towards losing our autonomy, and without autonomy, what do we even have left?

Free the People publishes opinion-based articles from contributing writers. The opinions and ideas expressed do not always reflect the opinions and ideas that Free the People endorses. We believe in free speech, and in providing a platform for open dialogue. Feel free to leave a comment.