Oscar Wilde was rehearsing a play one year, keeping grueling hours, all the way up to Christmas Eve. He showed no signs of letting up that night. Finally, one of the actors asked him, “Oscar, do you not recognize Christian holidays?” He paused and replied: “the only feast on the liturgical calendar I recognize is Septuagesima.”

It’s a funny statement because of the seeming obscurity of the term. Typical erudition.

And yet, the term was once not so obscure. The revamping of the calendar in the 1960s took it away. Tragedy there. The day marks the lead up to Lent. Now Lent is just sort of sprung on us with no preparation. With Septuagesima, we know, there are only three weeks until the fasting that begins on Ash Wednesday and extends to Easter, which, in turn, is nine weeks away.

Septuagesima, then, marks the beginning of a process of suffering, then death, then resurrection, and final glory.

I’m writing on Septuagesima, as it existed in the old calendar.

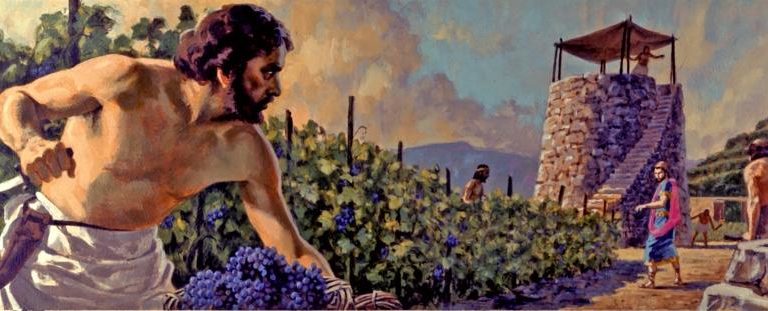

To really understand the implications of Oscar’s statement, you have to look at the Gospel lesson of the day, which is the awesome and mind-blowing parable of the laborers in the Vineyard. A vineyard owner wants to finish the harvest before nightfall, so he hires a group of laborers and makes a contract with each of them.

But as nightfall approaches, he realizes that he won’t be done. So he sends for more. Because it is late in the day, they are probably a bit reluctant. Maybe they thought they would never be hired. In any case, the vineyard owner makes a contract to pay them for a full day’s wages, even though they would only work a few hours.

The harvest is completed. Then he pays them all the same wage.

The people who worked their asses off all day are understandably annoyed, and they demand to know why the people hired so late get the same wages. The vineyard owner reminds them that it is his vineyard and he can make whatever contracts he wants. Plus, he points out, their complaints can only stem from resentment against others. They should be happy with what they received.

Why did Oscar like this story so much? Maybe he was making a clever joke about the long hours the laborers were working. Or one might suppose that he imagined himself to be one of the laborers hired very late in the day. Indeed he would wait as long as possible. Even to the very end. Nonetheless, his pay of salvation would be identical to saints who lived long and holy lives. There is comfort in believing that.

There are always other priorities for our day. We all want to wait, as long as possible. And we always hope that the glorious thing will still be ours no matter what else we do in the meantime. Thus is the nature of the mercy of God — ever loving, forgiving, generous.

Thus ends the lesson.

Is there a lesson in Septuagesima for lovers of the liberty? This election season seems to mark the beginning of a period of suffering. After so many years when liberty has been on the march, outrunning the state for so long, inventing new techniques for human liberation that no one imagined could exist only a few years ago, the climate has changed.

Politics has intervened.

We look at the lineup, and we see: opportunists, authoritarians right and left, proponents of the status quo and the prevailing ruling class, crazy people who barely contain their blood lust for using weapon of the state against their chosen enemies. It’s an awesome thought: one of these people will, one year from now, become the most powerful person in the world.

This is the Lent for liberty. These could be dark times. It seems only months away. How will we fare?

It depends. How strong are we? How determined are we?

Lent itself is an analogy of the long days in which Jesus lived in the desert, going without food and water and confronting temptation from the devil himself. He made it through, and came back to mobs who celebrated him for all the wrong reasons. Those same mobs would later turn on him as he hung on a cross.

In that same way, the cause of liberty is without food or water. It is being tempted by short-term fixes. Many of the people who only four years ago were attending rallies and hoping for a new leader to lead them to light now have the political bug, and they are turning to grim representatives of alien ideologies. They have scattered, losing hope in the original idea and instead adopting a kind of cynicism that says: if you can’t beat them, we might as well join them and get a pound of flesh.

One might say that the devil — the temptations presented by political control — has been unleashed. And it is going to get worse.

Can the cause of liberty endure these times? What is on the other side?

Let’s return to the lesson of the Septuagesima. It is the beginning of deprivation. And yet the parable of the day speaks of hope — the last hired still experiences the fullness of reward. The cause of human liberty might be that last hired man, tapped for service only once every other option has been tried.

Ten years ago, I never imagined that something so mighty and ghastly could come along that would so divert the progress we have made. And yet, here it is.

Let us remember that it is never too late in the day. We only need to wait for these times to pass. Be patient. The payout will be just as sweet. Easter is on the other side.

You’re coming around Mr. Tucker. You taught us that freedom and it’s quest are messy. Glad to see you’re there again because it’s going to get a lot more messy and “Easter” is but a dream for many of us. But it will happen.

You’re coming around Mr. Tucker. You taught us that freedom and it’s quest are messy. Glad to see you’re there again because it’s going to get a lot more messy and “Easter” is but a dream for many of us. But it will happen.

I do not want to sound millennialist, but I believe in the next 50 years everything is at stake: either we end up like 1984 or the world will see some kind of anarchy. Technology is accelerating so fast, and it is a double-edged sword. I’d give the odds 70/30 with anarchy the most likely winner.

What did Wilde mean? He probably meant his comment to serve the same purpose as the novel ULYSSES did for his fellow Irish writer, James Joyce, who once said of that he had put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant. It has been over a century since Wilde’s comment and folks are still puzzling over his meaning.

Getting rid of the 3 Sundays before Lent was possibly the most pointless of all the liturgical innovations of the 60s.

Jenny, are you advertising or trolling? In either case it is inappropriate here.